4.2: Bad Ux = Bad Data

or 'How Ben and I Killed iCommand'

I’ve got a mixed combat record. Ramadi has been leveled at least twice since I left it in 2005. The Taliban retook Afghanistan in late 2021, though they’d already retaken Zerekoh Valley earlier. Daesh hasn’t regained a 1/10th of the ground it lost by 2019, but it’s still kicking around and causing headaches.1 But, if I have one lasting impact, one confirmed kill that never came back, then it’s iCommand.

As Ben and I were prepping to head down to join the Army Warfighter Assessment 17 in the fall of 2016, USASOC headquarters reached out to our group commander and asked us to test out some new software.2 They were interested in purchasing a new COP tool to roll out across the entire formation.3 Seeking a ‘single pane of glass’, USASOC was chasing the Holy Grail of COP software. They were on the cusp of cutting a check for iCommand, and our commander volunteered our unit to test it out. I’m really glad he did, because iCommand needed to die.

iCommand suffered from a lot of problems, mostly because it couldn’t do the things the vendor said it could. First and foremost was displaying a map. We’d been warned that the software wasn’t done yet, and the contractor team hawking the software would need a little bit of time to get everything up and running. So, Ben and I tried to help where we could, and tried to be patient where we couldn’t really afford to. After a day without a map, we opted instead to draw one with dry erase marker on a giant wall of whiteboard paint. Ben pulled up Google Maps on to a projector and we traced our first COP so we could get necessary planning started. That analog COP was what we fought off of for the rest of the week.

One early sign of trouble was the make-up of the iCommand team. I think there were about five of them total, but I can’t say I ever saw more than one of them actually knee deep in the code trying to fix it. The rest of the team were salespeople, and they were trying to sell iCommand like Amway, hawking a program that was struggling to project a displayed map at the front of a JOC. In particular they were very excited to show off the giant 36” touch screen you could use to move around the map. Ben and I looked at the mega-iPad in a ruggedized container and didn’t know what to say. It was a cool toy, sure, but we still couldn’t display a map.

While their Ux might work with a touchpad, that was about the least demanded feature I have ever had — I still couldn’t give a shit about it even today. ‘How do I make it fly to a point?’ I asked one of the salesmen. ‘It doesn’t do that,’ he replied.

‘Fucking what?’ I asked. He looked as baffled at me as I did at him. Deciding I just hadn’t been clear, I tried asking my question a different way. ‘How do I input a grid and make the screen go to that grid?’

‘It doesn’t do that,’ came the same reply, at least a little sheepishly this time.

‘I kind of need it to,’ I explained. He paused in thought for a bit and then, sparked with an idea, suggested, ‘It shows you the grid in the center crosshairs at the bottom of the screen. You can drag the map around until you’re on the grid’.

It’s hard sometimes to explain computer Ux via text, so bear with me. What he was suggesting was the equivalent of you opening Google Maps, and instead of just searching the address you are looking for, you would painstakingly move the pin around the map until you found it on your own.4 Putting aside ‘it doesn’t do that’ for the moment, I decided I needed to meet him where I could. Our commander had been clear with Ben and me that we had to give the software a fair assessment.

‘Ok, how do I drop a pin?’, I asked, figuring that would at least help me aim.

‘Bookmark,’ the salesman replied. I stopped poking at the interface and looked at him.

‘I don’t want to bookmark anything; I just want to drop a pin.’

‘Booook maaark,’ he said, slower this time. ‘They aren’t called “pins” in iCommand, they’re called “bookmarks”.’

At this point I’d run out of that day’s patience. ‘You don’t get to just rename shit. That’s a chair, and that’s a table,’ I vented, pointing at both. ‘I don’t get to suddenly start calling them a swimming pool’.

Ben, to his credit, gave them more patience than I did. He spent an entire day trying to recreate the intelligence overlays his team had already made. It took him almost twelve hours just to reconstruct data that was already twenty-four hours old. At that pace he’d never hope to keep up with the fight.

A big part of iCommand’s sales pitch was it was going to take all the reporting data and auto-populate it on the map for you. After a week of struggling, the iCommand team finally connected all the ones and zeros, and it certainly did depict all the data. All the data. To quote Ben, ‘It was a kaleidoscope of shit’. The great irony was that the map was so full of data, you couldn't even see the map anymore, just a day after they finally figured out how to get one on there.

Ben came over and asked the team how his analysts could manipulate the icons. We’d long ago figured out how to break data across layers in KMZs, dynamically filtering by the data within, like a sliding time scale to only show icons from a certain time window. Levels of command could also be filtered into layers to declutter the display. The iCommand team shrugged off our request for similar features. This was Ben’s breaking point. ‘Now why wouldn’t you want to do that? It’s got all the data right there!’

In retrospect, while I was adopting my familiar direct attack, Ben was flanking them. The next night, when we gave our nightly briefing to the commander, we tried to use iCommand. I laid out all the reasons iCommand couldn’t do the things I needed to run operations, convincing my commander there were problems. But I think he was just as convinced the blame could lay with me.

Then Ben very slowly and methodically explained all the diligent work his team had done, over half a day, to display 24-hour old intelligence to our commander. He laid bare that we couldn’t enable the commander to make timely and informed decisions. Our commander asked Ben why he was hand jamming all this data in the first place. Wasn’t iCommand doing the import automatically?

And that’s when Ben executed the double tap.

He turned on iCommand’s COP and that Jackson Pollock of all the data. You could see the look immediately on our commander’s face: pure shock and revulsion. He was used to seeing how Ben and I used Google Earth to present. He wanted ‘The Ben and Erik Roadshow’. He politely asked, ‘Ben these're a lot of information on there. Can you just show me what you're talking about? Because I can't really visualize it.’

With the most innocent smile I’ve ever seen him give, Ben replied, ‘No sir, iCommand doesn't do that’.

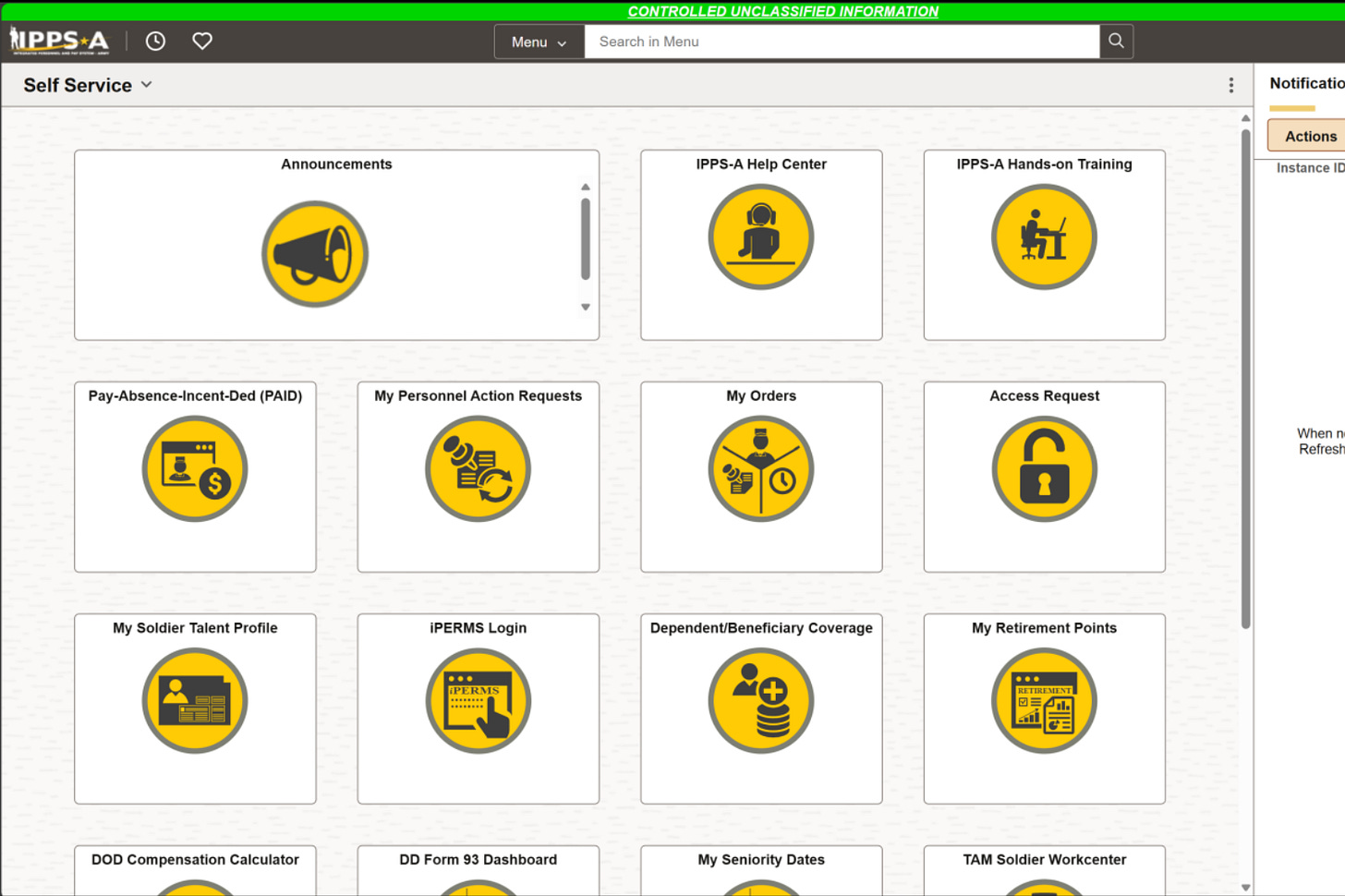

A Bad Ux gets you bad data, but it also gets you ‘a kaleidoscope of shit’. This is true across a lot of government software. Ux are almost always an afterthought, when they need to be prioritized at the outset. The iCommand team wasn’t even prioritizing it with us users desperate to give them feedback. The salespeople kept arguing with Ben and me that what we wanted wasn’t important. Not one coder sat down with any member of our unit and took our feedback. Because Ux was not a priority. The prime that was hawking iCommand wasn’t trying to solve a soldier’s problem, they were trying to lockdown five to seven years of guaranteed spend in the next POM cycle.5

But Ben also hit on one of the great fallacies of data: the great hope that the data itself is going to save us. The Primes selling ‘single pane of glass’ tools promise if we just get a good set of organized data all our problems will be solved. But data itself doesn't actually tell a story. You still need a person involved. It’s the interaction of both that helps us make sense of the data and drive our decisions. In my 21 years in the army, I have never seen anyone tell stories with data better than Ben.6 To the relief of our commander, Ben fired up the Google Earth overlays his team had kept up to date and finished the brief.

The day before the USASOC commander was due to visit, the iCommand team approached Ben and me. They let us know instead of using the regular commander’s update to brief him, there would be ‘some special effects’. The iCommand team spent the rest of the day rearranging our JOC so they could get their giant touch screen front and center and practiced presenting the scripted screens they were going to show to the CG.

Ben and I opted to preempt their brief entirely, redirecting the CG and his entourage into the room before our JOC — the one Ben and I had been sleeping on cots in throughout the week. There we sat down with him and laid out our issues with iCommand. The conversation went on for at least 45 minutes. Our group commander had told me to refrain from bringing up our back-up Google Earth COP, so we instead explained how and where iCommand didn’t work, and that when it did, it wasn’t any help. The CG let out a disappointed sigh, and looking over at his aide from a special mission unit, asked him, ‘What do you guys use?’

‘We typically use Google Earth, sir’, he replied.

As I sat up in my seat, I caught the sideways glare from my commander, so I tried a different tack. ‘Sir, I don’t think you can code a program that will give everyone what they want. You’re a three-star general. I’m a major on a group staff.’ I tried to explain how hard it would be to code a program that both of us could use in the divergent ways we needed to.

A COP is not just a displayed map at the front of a JOC. In fact, the team in the JOC rarely looks at the mega-wall screen. A real COP is a data fabric of all the intelligence, logistics, and operations of a military headquarters accessible to each member of the unit to interrogate and update from their own position.

‘I don’t need you to build me a house, I just need good tools’, I offered. ‘You get me good data tools; I’ll build you a house’. The CG thanked us for the feedback, and with the fifteen minutes remaining, he went next door and awarded command coins to a handful of our soldiers in the JOC. The iCommand team stood at the back, looking dejected as no one wanted to play on their giant touchscreen.

A few years later, I got to ask the USASOC G6 about iCommand. ‘Never heard of it’. SOCOM is still diligently throwing a lot of money at the defense industry trying to code their ‘single pane of glass’ COP. For a headquarters that still counts people via PowerPoint, I think that’s a lot like ice skating up hill, but I wish them luck. In the meantime, if you’re a coder who’s interested, my next post will summarize some of my Ux suggestions. If you’re in sales, I’m probably not the guy you’re looking to talk to.

Also known as the Islamic ‘Oops, I lost a state’

United States Army Special Operations Command. The headquarters of all ARSOF (Army Special Operations Forces), which includes SF as well as CA (Civil Affairs), PO (Psychological Operations, or PSYOP), the Rangers, and ARSOAC (Army Special Operations Aviation Command.

A common operational picture. Oten sought after as the ‘single pane of glass’, no one yet has made the Holy Grail of COP software. Typically mistaken by commanders to mean the projected or displayed map at the front of a JOC, a real COP is a data fabric of all the intelligence, logistics, and operations of a military headquarters accessible to each member of the unit to interrogate and update from their own position.

Program Objective Memorandum, which doesn’t really tell you anything, does it? The army is so bad at this. POM is basically the programmed and approved spend plan for a DoD unit going out to seven years from now.

Ben briefing enemy is like watching a cliff hanger episode from the Breaking Bad or Game of Thrones (the early seasons). You find yourself going, ‘Don’t stop there? What happens next?!’