I like the insurance industry. That’s probably not a popular opinion. Most people seem to have a very negative view of insurance firms. This mostly stems from health insurance which in the US is a train wreck for a myriad of interconnected reasons beyond this post. When I discuss insurance below, I’m referring to much more clean cut varieties like car and home where you opt into clear plans that detail what is and is not covered.

I like insurance partly because it is a very data driven industry, and also because it’s an industry which calculates, talks, recalculates, and decides — indeed it lives — in terms of risk.1

The underlying irony about insurance is that it's a bad purchase right up until the day before a crisis happens. Then it instantly becomes moronic not to have it. Sticking the landing on that wager is beyond most of us. Perhaps the best story of a group of people doing this is captured in the exceptional book and movie ‘The Big Short’. The engine of the 2008 crash — credit default swaps — are insurance.

That tension — between the logical decision not to buy and rational understanding it’s stupid not to buy — is at the heart of insurance. Most people who pay for insurance will never use it. The entire industry depends on this. The market can’t survive if everyone is cashing in their policies — which is part of why health insurance is tricky.

Home insurance can be pretty expensive. The higher cost is because even ‘cheap’ houses are incredibly expensive purchases and the chances that they will be damaged, while not high, are for the industry a somewhat moderate risk.

Cars are even riskier. Driving is probably the most dangerous thing you do every day. Cars are so risky that in almost every US state it’s illegal to drive a car without insurance. As a fraction of your loan payment, car insurance is a much higher percentage than homeowner’s insurance.2

Conversely, renter’s insurance is incredibly cheap, often less than $10 a month. And yet, young First Lieutenant Davis didn’t think it was worth the trouble to pay for. By dumb luck, the landlord for my first apartment wouldn’t approve my lease unless I got some. This was lucky because years later, in the middle of a PCS, my car was broken into and my belongings stolen. Car insurance only covers the car, but that renter’s policy reimbursed me for everything from the new laptop down to the Michigan State t-shirts I’d lost. In truth, I’d actually forgotten I was still paying for renters insurance until the car insurance company reminded me.

The main reason renter’s insurance is cheap is because the risks aren’t very high, and even if you do submit a claim, they aren’t often terribly expensive. Your renter’s might cover up to $400,000 worth of your stuff, but you don’t typically lose all of your stuff at once.

So why am I taking time to write about all this?

How Defense Is Similar To Insurance

Defense shares a lot in common with insurance. I first encountered this idea while listening to the New York Stock Exchange’s head of security about a decade ago. He was explaining how his job was really about providing predictability. From the bollards on the streets outside to the cyber defenders behind desks in the basement, the purpose of all that security was to provide firms and traders the calm certainty that regardless of what horrible thing might happen at any moment, the next day would be another normal trading day.

Now states, like those traders on the floor at the NYSE, invest in a lot of things. Most investments are done with the goal of making more money later: stocks and bonds, but also roads and bridges, education and healthcare. Governments put money into these projects with the belief they will garner a greater return on that investment. For the US our investments in programs like Medicaid and Science R&D have seen returns between $1.78 and $2 for every dollar invested.

Defense isn’t like that. Defense is not a revenue generator. Even if you add in the jobs in the military industrial complex and the value of foreign military equipment sales, the costs of defense don’t come close to breaking even. Defense, like insurance, sits over in the expense column. We don’t buy insurance to make a profit.3

The military’s primary role is not actually to win wars. That is certainly in the statement of work, but principally, the military is an insurance program. States invest in their military to hedge against risk — some of them existential — for the same reason the NYSE has a head of security. It is to convince the public that they live in a predictable world where they can make long term bets.

Defense encourages citizens to make long term bets like where to build a factory or where they want to go to school and where they want to raise their families. If you live in a war zone, people tend to make only short term bets. I saw this back in late 2008 when the local Iraqis finally started repairing the flagstones outside the Baqubah City Center. It only came on the heels of three months of quiet after almost a year of monthly suicide bombings at the site. This was one of the first signs of improving security in the province.

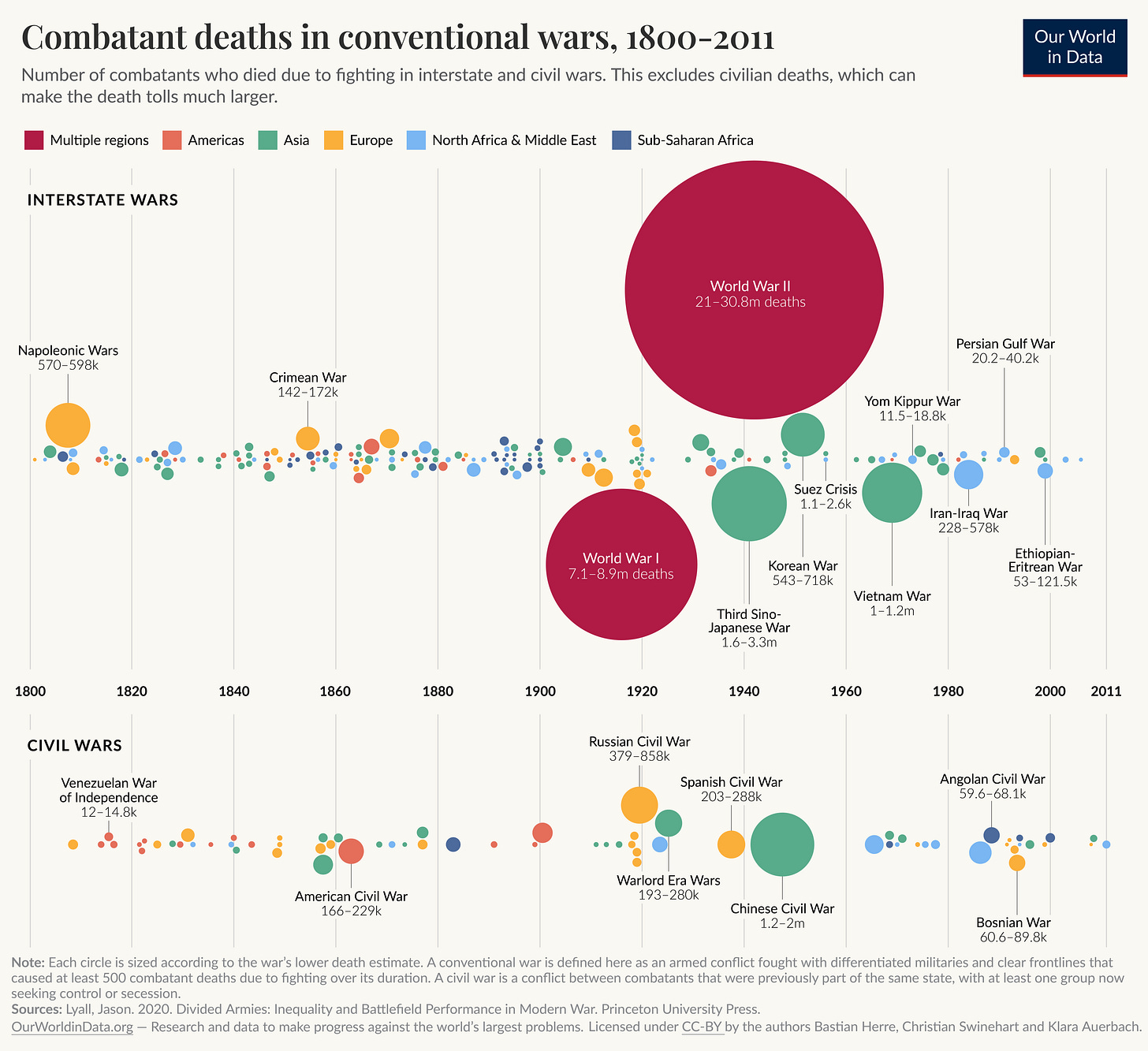

War is what Nasim Taleb calls a fat tail risk. This is because wars don’t happen along a normal distribution, but instead happen at ‘beyond three standard deviations of the norm’. That’s stats speak for very unlikely but with huge impact. If you look at a chart of human history, you’ll find very few years — often barely a couple months — where there wasn’t some war going on somewhere. But for any given country’s military, the overwhelming majority of those years were ones of peace.

There’s only a few blotches on the chart above where even half the world’s armies were invited. For most of the world, investing in the military was buying an insurance policy you never cashed in.

Over the last 80 years, since the end of the second world war, a lot of our allies spent a pittance on their defense. They did so for a variety of reasons, which included the US at times discouraging them from spending more. We did this at times overtly, like when we extended our nuclear deterrent; but also more and subtly, through selling US developed arms. When you buy US weapons, you aren’t developing your own domestic capabilities and industries.

These allied states also made the economic decision that 'defense homeowners insurance' was a unnecessary investment. Instead, many countries opted to invest their money in those other profitable endeavors. In the case of Europe, they instead funded a much more generous state, investing in healthcare and education and infrastructure — all things with an anticipated RoI. And they’ve done it for roughly four generations.

Between 1945 to 2022, those bets have turned out to be a correct one. In all that time, the NATO 'catastrophic war insurance' only got cashed in once: when the US invaded Afghanistan.

In Australia, where I just left, they bet that the economy and natural disasters were more likely to topple their government than any foreign power. So the Aussies opted to only invest marginally in 'catastrophic war insurance'. Like Europe, for the last 80 years, this was the right bet. New Zealand bet even harder, in no small part because they knew Australia would absorb any adventurous foreign power before it got to their shores.4

But there’s risk cost in four consecutive generations making the same blind bets. The biggest risk is that you can forget you’re even making a risk decision — the ‘It’s always been this way’ fallacy. A second is it’s harder to take things away once given. Kahneman and Tversky coined it ‘loss aversion’ when they found we really don’t like to give up anything we have, even if we’ve only had it less than an hour. This makes reallocating money out of investments and back into the expenses column harder.

A third risk which compounds these two is so primordial it’s evolutionary. Richard Dawkins details the ‘Dove versus hawk’ dilemma in his book Selfish Gene. The theory examines the ratio of aggression versus peace seeking behavior in a population, noting that the ratio is always in flux. If the number of aggressive individuals — ‘hawks' — in a population gets too high, they can risk species collapse. This drives selective pressure for less aggression. But if the number of peace seeking behavior — ‘doves’ — gets too high, then the payoffs for hawks grows. The distribution is always moving, as populations seek out an evolutionary stable strategy.

States can follow a similar rise and fall. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, and then again in 2022, is just one example. The principle commentary from many in the west was ‘State’s don’t do this anymore’, failing to realize their pacificism actually made Russian aggression more likely. They’d forgotten for most of European history Russia’s behavior was very much the norm.

Ukraine’s decision to surrender their nuclear weapons in 1992, in many ways the ultimate insurance policy, looks like a very poor bet in retrospect. Indeed, it seems like we are headed to a world where getting your own nuclear insurance policy is a wise investment. Far better to be North Korea than Libya, Syria, Iraq, and potentially Iran.5

The challenge for most US allies is to overcome those four generations of habit and to shift their domestic investments into insurance expenses. In Europe, perhaps unsurprisingly, the pace of change maps fairly well with ‘proximity to Russia’. But despite the scorn heaped on our allies for spending less all these years, for the last eighty they made the right bet.

How Defense Is Different From Insurance

Defense, however, is not exactly like insurance. Most people don’t look at their insurance policy as an excuse to set their house on fire.6 But in the 1990s, US ambassador to the UN Madeleine Albright asked in frustration, ‘What’s the point of of having this superb military that you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?’

While investing in the defense can lead to military adventurism, perhaps the biggest difference between normal insurance and defense insurance is you only have to pay normal insurance their premium once. When your house gets burned down, the insurance company doesn’t immediately demand you pay them more money to reimburse you. But in the advent of conflict, the first thing defense does is ask for more money.

Insurance also doesn’t need to buy platforms. State Farm doesn’t need submarines, bombers, tanks, or satellites. Those platforms take time to develop both from a manufacturing standpoint and from a doctrinal one. Tactics need to be developed, taught, and trained. Upgrades need to be tested and implemented.

80 years of investing in war platforms is its own kind of habit. Just about every major war starts off poorly. Often states must scrap old tactics and weapons for new ones. Militaries, conservative organizations almost by their nature, are slow to accept change with a well documented habit of refusing to see the next war out of nostalgia for the last one.

‘The only thing harder than getting a new idea into the military mind, is getting the old one out.’ - B H Liddell Hart

Across history militaries have an almost perfect track record of getting the next war wrong. We almost inevitably have to to go back and relearn how to fight with new tools. France’s Maginot insurance policy was completely circumvented by new tactics after all.

So, while we may decry our NATO allies for their 80 years of not investing enough in their own defense, they did not waste those 80 years investing in the wrong platform either.

Breaking Down Defense

Ukraine, caught in an existential struggle the US has not known in two hundred years, is showing itself much more capable of adapting than we are. Programs like their Brave1 have unrecognizably different acquisition process, one that incentivizes and incorporates local suppliers into a market with local units. It is probably not something we can currently replicate in the US, since that existential risk helps hold Ukranian defense suppliers accountable. In the US, where we struggle to compel a defense contractor to even deliver a system on time, it is unlikely we can adapt and innovate at the pace Ukraine is.

That pace of technological change has been accelerating over the last decades. It shows no sign of slowing down. Death is getting cheaper every day. While large military platforms still have their role, and can do things cheap drones couldn’t dream of, cheap and innovative platforms are having their own strategic impact on the world.

NATO, after underspending for decades, is now heralding ‘5% of GDP’ as a new target.7 But what does ‘5% of GDP’ mean when it’s not clear what you’re buying? Estonia could buy a lone B2 bomber and meet their spending target, while not having any pilots, or any of the requisite ground forces they would need to defend against a Russian invasion.

Ukraine, meanwhile, just inflicted billions of dollars of damage on Russian strategic bombers with drones that barely cost $2k a piece. Those same drones could do similar damage to our own Air Force and Navy in a similar style attack. As the Economist put it, how do you ensure 5% of your GDP isn’t ‘just building up yesterday’s army’?

In insurance, when risks increase so do prices. Air defense is expensive but Ukraine has shown us all it is critical. So is EW. Those risks aren’t just overseas in foreign wars. They are at home, in the ‘deep area’ where many countries used to assume they were safe. It is going to be hard to convince a public accustomed to not buying defense insurance that it’s worth the cost. What happens when people no longer trust that regardless of what horrible thing might happen at any moment, tomorrow will be ‘just another normal trading day’?

The future looks gloomy. And expensive.

All sorts of groups can deny climate change, but insurance companies certainly believe.

Assuming you don’t live in a place where climate change is going to destroy your home.

If you do, that’s called insurance fraud.

Given that New Zealand was one of the last places populated by humans on earth, this was a sound wager.

A few weeks later, the impact to the Iranian nuclear program is unclear.

See above re: Insurance fraud.

NATO’s 5% is also a mostly made up figure since 1.5% of that can basically be spent on just about anything with even a tangential tie to defense.

The renter’s insurance anecdote is gold: clear, personal, and makes the point stick. Most people only realize the value of insurance when it saves them from a mess they didn’t see coming. Defense works the same way, but with a longer time horizon and much higher stakes.

What stood out most to me is the framing of defense not as ROI, but as a bet on predictability. That flips the conversation. Defense spending isn’t about growth, it’s about buying the conditions for growth. But if that’s true, then the platforms we buy should reflect the real risks, not nostalgia.

What I'm left wondering: how do we shift the conversation—politically and culturally—from “how much should we spend?” to “what kind of defense insurance are we actually buying?”