Z.12: Curiouser and Curiouser

I had a spark of insight while I was sitting in a room of fellow Colonels and Navy Captains last month.

We were in a pro-dev course designed to help military officers manage our transition into the senior leaders who are charged with driving change in our militaries. During a block of instruction on future tech trends, it became clear pretty quickly the majority of the students lacked experience with current AI/ML tools, despite these tools being available to experiment with for free since 2022. The questions my fellow students asked implied many were looking for excuses to continue their ignorance.

‘It all just hallucinates, right?’

‘I heard there’s a study that people who use AI are less informed.’

When the instructor asked who had used an LLM or AI tool in the last month, only a couple hands went up. Most of the fellow O6s in the class had not actually used any of them at all.1

Meanwhile, when I log on to NSTR each morning — where there are three separate channels covering AI/ML topics — the junior officers quickly lose me with their depth of understanding about not just how to train models but also the convoluted process to get approvals to actually use them on government networks. This is what prompted me to sketch out this chart in my notebook:

This is a problem. The population of officers empowered to drive change lack the information the army needs to guide it toward the future. This deficit is a result of the military’s promotion system, which promotes off time in service, not knowledge. The underlying theory is the longer you’ve been around, the more relevant experience you’ve amassed, and thus the more rank you justify. In some cases this works exactly as expected. But what happens when the experience you have isn’t the experience we need? What happens when there’s a different room, filled with younger or different people who have more relevant experience?

In the chart above, if you replace AI with ‘data literacy’ you’ll see a similar distribution. Or, alternatively, let’s imagine a chart of knowledge and experience in making and fighting with cheap drones. On that chart just about any junior Ukrainian NCO is on the far right end of the distribution and pretty much all the US Army officer corps is sitting around zero. The average trench in eastern Ukraine has more drone knowledge and experience than the entire US Army combined.

More and more of the skills we need as an army aren’t found within the ranks of our leadership. This is particularly concerning because the pace of change isn’t slowing down, or even staying static. It’s accelerating. We don’t need colonels to be experts in AI, or data, or cheap drones, but we desperately need them to be voraciously curious in these fields. We can’t sit back and wait for PME to educate them, we need relentlessly self-driven learners.

‘Whatcha reading for?’

The O6 grade is the rank charged with driving change in the military. But in too many rooms full of O6s over the last year, there has been a distinct lack of curiosity. Indeed, when I shared the above chart on LinkedIn, I was surprised by people who downplayed the problem.

One self-described ‘strategic thinker’ provides an example of the malaise:

Is the Colonel's job to be curious or to lead and mentor people they lead to be curious? Shouldn't they be the ones cultivating curiosity not necessarily the ones with the preponderance of curiosity?

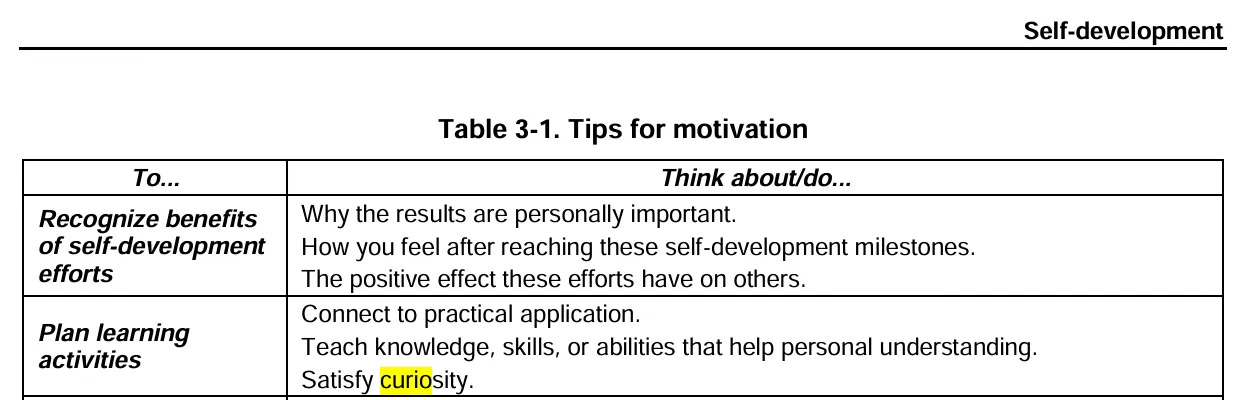

I’ve also seen charts intended to map the volume of learning an officer does over their career. These typically suggest that ‘learning’ diminishes to a nearly invisible slice by the time you reach O6. The army’s manual on developing leaders, FM 6-22, don’t seem to disagree. The only mention of the concept in FM 6-22 is ‘curiosity’, which is only given a single passing comment in a table about self-development:

The pervasiveness of this incurious mentality is pretty disturbing. What’s worse, because of how we promote, the attitude that a senior officer doesn’t need to be curious leeches down the grades until you have even junior officers denigrating reading as some ‘intellectual’ pursuit. It’s a great Bill Hicks bit, but as a second lieutenant sitting atop my Bradley in Korea I actually had a senior officer walking by ask me ‘What are you reading for?’

The army doesn’t naturally produce curious leaders. If anything, it tends to breed them out of our formations. Einstein once quipped, ‘It is a miracle that curiosity survives formal education.' You’ll find no more formal education than the one the military provides. We reduce everything we can to drill and rote, and rarely reward innovation. This attitude would work fine if war were a static thing that never changes, some ancient and unchanging art. But war relentlessly evolves. The military instead tends to discourage free-thinking, while almost never punishing conformity, even when it leads to the deaths of thousands.

Contrary to the above cited excerpt from FM 6-22, we need leaders who cannot ever satisfy their curiosity. Returning to Einstein, ‘The important thing is not to stop questioning; never lose a holy curiosity’.

The army probably can’t run on every solider constantly questioning everything, but we need curiosity desperately in our senior-most leaders. Unfortunately, the military has a plethora of incurious leaders these days. Last spring, it was a four-star general who told a room full of us future battalion and brigade command teams not to worry about drones because ‘Our tanks drive fast’. Incurious leaders presume we don’t need to worry about drones because ‘They've yet to meet a full spectrum, robust defense’. Incurious leadership is why most of our formations still only move at the speed of PowerPoint instead of data.

It actually takes a lot of things for curiosity to thrive. You need time, and safety. Curiosity doesn’t really bloom until you’ve satisfied the first few layers of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Mentorship can be invaluable. Not everyone gets these when they’re young. But colonels are sitting at the top of that pyramid.

The Walled Garden

There’s no way to move laterally into the senior grades of the military. Colonels don’t need to fret about some younger, brighter officer with new experience coming in from their flank to take their job. The only way to be a colonel is to be a lieutenant colonel first, and a major before that, and all the way down the line back to a second lieutenant. Senior ranks are a walled garden. Too few colonels, looking around themselves and their peers, take the time to ponder where the rest of their peers ended up.

Those of us who stay in and promote in the army tend to think we’re the best of our peers. We imagine a bell curve of army talent like this:

One of my favorite army peers redrew this chart for me:

I’ve done plenty of things to piss people off throughout my career, but nothing has ever had a more visceral and emotional response than when I show senior officers that chart. Colonels and generals get really angry just at the suggestion it conveys.

Another friend of mine, Zach Griffiths, recently published a great piece which included the line: ‘You Don’t Need Permission to Be Curious’. Since I was already working on this post, I reached out and we had a wide-ranging discussion about the role curiosity plays in an army career. He’s actually the one who prompted me to check and see what doctrine said — or didn’t — about curiosity. As we talked I brought up my recent post where I decried the ‘maximum standards’ the army uses for our fitness tests.

Zach responded with a great insight. ‘We have it backwards in the army. Imagine a business or sport where there was an age minimum to be a leader and a performance maximum.’

The war college tries hard to beat the drum about how we need to be a ‘lifelong learner’. They do it so much that it kind of gives up the game. Maybe because trying to convince an officer in their mid-40s to suddenly be curious is a fool’s errand.

As an institution, the military can actually seem to be surprised to discover other organizations learn. I’ve sat in far too many briefings where someone tried to sound profound by saying ‘You have to understand, ____ is a learning organization’. Al Qaeda, The Taliban, ISIS, Boko Haram; insert your enemy, I’ve heard it for all of them.

All organizations are learning organizations. It’s half of what organizations do: they capture, share, and improve knowledge. Denny’s is a learning organization. Non-learning organizations die out, or get bought out and sold off. That is unless they live in a walled garden.

‘What got you here won’t get you there’ is another refrain we get told a lot at both the senior service colleges and at the myriad of brigade level pre-command courses. I think it’s absolutely true, but the cautionary tale is there in the telling. Many of us won’t make the turn. We’ll stick to our experience, retreading over what we know instead of embracing the discomfort of not knowing.

Michelangelo and the Marble

I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.

The quote is almost certainly apocryphal, especially since it never showed up anywhere until three centuries after Michelangelo’s death. But it reflects how a lot of officers in the army think of ‘great leaders’ — junior officers of unmatched raw talent that just need the rough edges rounded off with experience. The idea is the great leader is born, not made.

Except that’s not how we grow as leaders. The process is much more additive than subtractive. We’re not marble busts, we’re seeds. We have kernels inside us, but we need a lot of external resources to germinate. We need feeding and watering and time and a ton of luck.

My early lieutenant years, in particular that one in Ar Ramadi, fundamentally changed me as a person, never mind as an officer. Perhaps the most impactful thing I left Al Anbar with was a deeply uncomfortable awareness of just how much I did not know. I spent an inordinate amount of my time during the infantry captain's course in the library, acquainting myself with the wealth of knowledge about insurgencies within that heretofore I was unaware of. I had graduated the infantry officer basic course in 2004 with the idea that there was a new thing going in Iraq called ‘4th generation warfare’, only to come back in 2006 and discover plenty of books on insurgency, many going back a hundred years.2

Curiosity has been key to my self-development ever since. Not everything we need to learn is cutting edge. That’s one of my favorite things about the articles Zach writes. He doesn’t always write about some novel or original idea he’s come up with. Instead, Zach continuously digs through the archives of lost knowledge — the lessons written down but not learned — and unearths the secret to winning a battle on the Polish-Lithuanian border, how politicization threatens our profession, or the ultimate recipe for an old fashioned. That is when he’s not campaigning to change the army’s culture to one where we read and think and — of course — write. Zach is a deeply curious person.

There are others out there. A junior field grade recently published with MWI ‘Encouraging Self-Development in Data Literacy’. Meanwhile, a fellow USMC Colonel published a great piece about innovation. More than just saying we need more, he laid out solid outlines for different kinds of innovation, and critically, ways create the culture and systems that actually generate them. Spoiler alert, commanders play an outsized role.

We can’t simply outsource innovation to mavericks on the fringes of the professional community, important as they may be in the process. Innovation requires the commitment of credible and respected senior officers—consummate insiders—to drive it from ideation to implementation.

The army is trying to encourage the uptake of data, but I think the efforts are trapped in a sort of valley-of-death. The Army War College recently announced their two-day executive course “Data to Decision in Warfighting” (DDWF). The stated goal is ‘to equip senior army leaders with essential data literacy skills for warfighting decisions’. I don’t think you can learn data literacy in two days. You certainly can’t learn much more than you could all on your own if you were just curious.

Dunning–Kruger Colonels

If anything, I’d suggest officers should be more curious as they promote, not less. After all, a brand new lieutenant lacks the experience to help guide their curiosity. This is why we give them officer and NCO mentors. Those mentors help guide that curiosity and keep lieutenants from killing themselves, or worse, their soldiers. But as you grow older, you have the benefit of experience to steer self-discovery.

Meanwhile, as you promote, the things that you know — and critically what you don’t know — impact an ever larger group of people. The impact radius of an incurious colonel can be an entire brigade.

Coming back to that ‘strategic thinker’ above: how is leaving curiosity to the junior officers going to help that incurious senior leader decide which equipment to acquire, or how doctrine must change? Having worked in the the G8 — the army’s department dedicated to funding, fielding, and equipping — I can assure you, no one was checking with the captains on which equipment we should be buying.

Agency magnifies the impact of curiosity. And promotion increases your agency in the military. Colonels have much greater power to pursue things that interest them and the rank to actually drive their organizations in those direction.

Think about the best business leaders out there. Are they incurious? Does Eric Schmidt, who is 70 years old, strike you as incurious? I’ve listened to Nilay Patel interview easily a hundred different CEOs on his Decoder podcast, and not a single one has ever said ‘curiosity is someone else’s job’. The difference here is, outside the military, you can’t survive as an incurious leader.

But the lack of curiosity is not uniquely a military problem. Other fields, in particular those ‘professions’ with entrenched hierarchies based on time of service, suffer from similar stagnation. David Epstein recently introduced me to the ‘Einstellung effect’ in a post he shared on his substack. He raised a 2016 study that showed why this led to more experienced therapists being worse at their jobs:

“There’s a lot of research on whether or not therapy works. We find over and over again that it works. It does pretty well, it’s got good effect sizes, all of that. The problem, as near as we can tell, is that more experienced therapists just do not have better outcomes than newer therapists…The best piece of research I’ve ever seen on it was 2016 (Goldberg), it actually suggested that therapeutic outcomes got slightly worse as the clinician got more experienced.”

Why? As Epstein argues in his post in some environments, ‘…people often gain confidence without gaining skill — a dangerous combination. Perhaps that can help explain why experience alone doesn’t predict better outcomes in therapy.’ Experience can be hugely impactful. Experience is why I don’t ascribe to that Michelangelo Marble model of leadership. Experience adds to who we are. Its the soil and sunshine and time that grow us as leaders. But you still have to ask yourself, experience in what?

Experience is also what gets you off of ‘mount stupid’ and descending into the ‘valley of despair’ on the Dunning-Kruger curve. Only curiosity gets you climbing back out the other side.

I have over 20 years of experience. Like many of my peers, much of it is focused on counter-insurgency. You’ll hear veterans of my generation constantly brag about our ‘21 years of combat’. But 21 years of ‘experience’ didn’t teach us how to fight a peer military. This was laid bare when in early 2020 I sat in a JOC while a barrage of ballistic missiles were fired at US bases in Iraq. My entire career, starting with that first assignment in Korea and running through my command in Okinawa, every operational war plan I’ve been assigned to begins with expected ballistic missile barrages. And yet, in early 2020, no headquarters in the theater was ready for ballistic missiles.

Curiosity matters more, not less, as we age and promote. Our colonel class is selectively bred, and our generals are all picked from among the walled garden we insulate them in. You can’t expect a trait not present in the former to suddenly appear in the latter. As leaders, we owe it to our soldiers to be curious. To never sit back and rest on our ‘combat experience’ as an excuse to not know something.

The military uses letter and numbers to standardize ranks across services and other nations. So while in the Navy an O6s is a Captain — which is an O3 rank in the army, USMC, and Air Force — other services call O6s Colonels. The ‘O’ stands for officer.

Of all the books I discovered in those six months, Tom Barry’s ‘Guerilla Days in Ireland’ is still my favorite, and one I loan out to junior officers regularly.

I can’t help but attribute the development of this culture to our personnel and promotion policies.

Most Soldiers remain in one location for less than three years and in a specific role for under two. This short timeline limits both the opportunity and incentive to learn deeply or experiment and innovate in a meaningful way. Many say that by the time you understand your job, you’re already moving on. Long-term stewardship and innovating to improve an organization over time are not incentivized when you only need to do well these next 24 months, and you'll never see the fruits or bear the consequences of your service at that assignment again.

I don't say this to imply COLs are self-centered or don't care about innovating, but I think it at least subconsciously affects the way senior leaders who have operated along this paradigm for two decades think.

Sir,

I know it's tangential to your point. But the Microsoft Study on AI and Cognitive offloading is a significant issue we have to deal with if we want to use AI. It should alarm us that we seemingly become less curious the more we trust in and use effective AI. I get your point is the leaders in your peice haven't read that study, but it should be mandatory in our line of work.