You don’t always get it right the first time.

Four years of data coding and thinking underlie the Harding Project. I started with a focus on my branch magazine, Special Warfare. Taking lessons from my failure to renew that outlet, I looked more broadly and found there was an Army problem. The journey through failure and following my curiosity led to the pile of data that provided the expertise and credibility that now underlie the Harding Project.

The failed first time

I’ve been interested in the health of the Army’s journals for years. In 2019, frustrations with a lack of response from Special Warfare led me to look into that outlet’s health. It published sporadically. It didn’t spur back-and-forth on the topics that mattered. It was absent on social media, except when SOF News would highlight a new issue. As Special Warfare struggled, the Special Warfare Center and School launched the great Pineland Underground podcast and my friend Kyle launched the Irregular Warfare Podcast. The demand was there, but Special Warfare wasn’t filling it.

But improving Special Warfare would require convincing leaders at the Special Warfare Center and School that (1) our journal could perform better, and (2) that this was worth doing.

I set out to make the case. Having read a bunch of Special Warfare back issues and more dynamic outlets like War on the Rocks, I decided to measure Special Warfare’s performance against six criteria ranging from regular publication to a balance of informative and argumentative articles. Based on these criteria, I coded 18 issues and 296 articles on the type of article, the author, the article length, and the topic. With data in hand, I wrote a white paper and sent it to the Special Warfare Center.

All this took a while. The frustrations of 2019 became a paper by the spring of 2021. Despite sending in a polished white paper, the timing was poor. The SWC chief of staff departed for a new job as I readied for a deployment. Quality data meticulously coded was not enough. That effort lost steam. But it did make me question whether the problem was a Special Warfare problem or an Army problem.

An Army problem

While the efforts with Special Warfare didn’t go anywhere, I started to poke around. Infantry’s stats on DVIDS were pretty sad: an average of 5.4 downloads and 905.4 views. Infantry wasn’t on social media, where outlets like the Modern War Institute had 78.6k followers. The Army’s other journals were all more like Infantry than a modern web-first, mobile-friendly platform.

I’d learned a few things from my Special Warfare failure. You could get a lot of data just by looking at the issues, but coding each issue took about 30 minutes, meaning that just coding Special Warfare took at least nine hours. I would not be able to code the same way with hundreds of branch magazine issues.

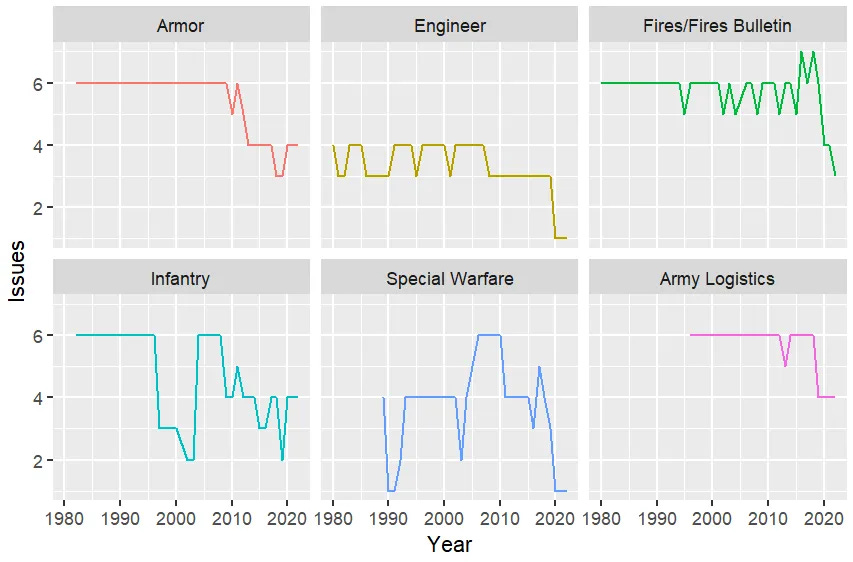

So I focused. I selected issue length and journal staffing as my key metrics. I also selected seven journals with available back issues. Thoughtful selection of my data structure let me analyze at a variety of levels: for each issue, I coded the journal’s name, the year, the issue number, and the number of pages. This allowed me to analyze the total pages of all outlets by year, or the change in Engineer’s number of issues per year (see above), or the change in Armor’s pages per issue. Journal staffing was a similar story, focusing on the different roles in a variety of journals over time. In all, I found that the journals published less, less often, and more erratically than decades previous. They were dying.

Despite these reams of data, it wasn’t enough for a knockout case. To understand authorship patterns, I also scraped authors from branch journals, Military Review, Parameters, MWI, and War on the Rocks. To understand whether any of these writings were making a difference, I studied citation patterns in the Army’s journals and Command and General Staff College monographs. There’s a lot of data.

The policy window

Confident in my findings, I wrote “Bring back branch magazines” for the Modern War Institute. As I thought through my recommendations on what to do about the Army’s diminished journals, John Kingdon sprang to mind.

Kingdon’s policy window framework helped me think about fixing our journals in a new way. Rather than just offer milquetoast conclusions that the Army should think harder about the condition of its journals, Kingdon’s framework asks whether there is an agreed upon problem, a policy to fix the problem, and the right conditions (or small-p politics) to drive action. “Bring back branch magazines” would help others see the Army’s journals as a problem worth fixing. I was pretty sure I had a solution. But organizational politics? I wasn’t sure about those, but I knew there was a new Chief of Staff of the Army taking over soon. Considering it a Hail Mary, I recommended that the Chief of Staff’s transition team consider the issue. They didn’t.

But then I got a chance.

I found myself in General George’s office. On the spot, he asked about the Army’s journals. Though the meeting was unexpected, the data behind the Harding Project was less important than the confidence and credibility that came from years of reading and coding back issues. And now the Harding Project is running hard.

Fascinating stuff. I’ve loved watching this evolve. If any of you need help with things like scraping, cleaning data, extracting information, programming, AI, or anything else then I would be happy to assist.