Click here for the rest of the series.

Last spring, I went to three different pre-command courses. One common theme I found across all of them was fellow colonels and sergeants major who said they couldn’t run anymore because of their knees. Too many years grinding out miles on pavement, doing the slow shuffle up and down Ardennes as the 18th Airborne chorus blared down at them from speakers. ‘C-C-C-130 rolling down the strip…’

They didn’t look particularly pleased with me when I told them I didn’t run, and they actually didn’t need to in order to still confidently pass the ACFT. For many of them, it was clear their fitness days were behind them. But I tried, none the less, to introduce them to two new tools they could use even with their worn down patellas: a rower and an assault bike.

Weights are pretty much the best way to take your gains to the next level. They take a cardio workout and make it anaerobic by amping up the intensity. You get more gains in less time. But weights can be intimidating for people. I concede there are people out there who don’t have the coaching that ensures they don’t end up injured through bad technique and overuse. Your first stop should be at your local strength coach at a THOR3 or H2F facility.1

But there’s pretty much no excuse not to use a rower or an assault bike. I’ve never actually seen anyone hurt themselves with either. They're such good pieces of kit that despite knowing how to clean and snatch and jerk weights, I still use one of these two torture training devices in every session I do, often more than once. So, without further ado, let me introduce you to your two new frenemies.

Row, Row, Row Your Boat

I first got on a rower because of burn pits. I was already not a fan of running by the spring of 2008 when I deployed to Diyala, Iraq, but the fumes drove me indoors. Having grown up a computer nerd, I was well aware that breathing in atomized PCB (printed circuit boards) was not a good thing for your long-term health. Unfortunately, FOB Warhorse wasn’t big enough for you to ever be terribly far from the camp burn pit.2 There was always a hint of that acrid taste in the air; it just got particularly foul when you shuffled right past the smoldering cauldron.

I tried the treadmills in the camp gyms first, but for reasons I will never understand, the main gym positioned their machines so that they were pressed up against the walls along the perimeter. This meant there was nothing to look at but the whirls of plywood wood grain two feet in front of your face. The camp’s smaller gym had their treadmills facing a wall of mirrors, which somehow was worse. I spent the entire time wondering, ‘Why do I look so weird when I run?’

Thankfully, our company had its own little pocket gym inside our compound, and in the back was a Concept2 rower. Knowing not a single thing about how to use one, I jumped on anyways. I think I settled on 3200m as a goal for no other reason than the familiarity of the two-mile run, but I figured the time it would take would be comparable and set off.

It was not.

I’d spent my first five years in the army bouncing just under and just over the 13:00 line on the APFT two-mile run, which is the 100-point line for those who never took one. Plenty of times I was frustrated to find out I’d run a 13:01, knowing full well that :01 second was in the tank somewhere. But there in Diyala, 13:01 on the rower left me in a puddle of sweat and the soul-certain knowledge there wasn’t anything left untapped. I was a convert.

The only problem was I didn’t know a damn thing about rowing. That wouldn’t come until about a year later when I was working out at Tacoma Strength. Leon Aldrich, one of our coaches, gave us a 10-minute row for distance set, and because it was one of the last classes of the day, he joined us, sitting down on the rower next to me.

Now I had no problem being beaten by Leon. He was way fitter than I was (am?). The guy was one of the owners of the gym after all. Still, when we were done, I asked him how far he’d gone and found he’d bested me by about 1,000m.

‘You’re cycling too fast. You're not pulling right,’ he told me. I was averaging about 35 spm (strokes per-minute), so I asked him what he did his at: 25.

As my breathing returned to normal, and with it my ability to do basic math, I worked out I’d done 100 more pulls only to come up 1,000m short. Clearly, I was doing something wrong. Leon showed me.

Rowing is a deadlift. Don’t believe me? Get yourself setup in a good starting position — back straight, hips canted slightly forward, hands holding the grip that’s about shin height, feet shoulder width apart — and have a friend take a picture. Turn that pic 90° and you’ll see it. Deadlift.

There are basically four counts to the row: the deadlift pull (legs), the core pull (back), the final pull (arms), and then the recovery. Every one of those pulls is important, but they get weaker in sequence. There’s a great drill you can use to see what I’m talking about.

Zero out the distance and then do ten pulls on the rower, but only with your legs. No back movement, arms locked out straight in front of you. Check your distance. Reset the erg and do ten more, only this time, only the back.3 Legs and arms stay locked out. Finally, do one all arms, no legs, no back movement. You’ll see each set of ten travels a shorter and shorter distance.

When you see someone cycling on the rower at 40+ spm, they are almost definitely doing it wrong, typically because they’re cutting out their legs, the powerhouse of the pull. Your legs have about 2.5 times the muscle mass of your arms, which gives them all kinds of power to pull with.4 So, while you don’t want to skip any part of the pull on the rower, definitely don’t skip the first part.

One way to measure this is to look at the interplay between two numbers on the screen. One is your strokes per minute. The other is your 500m split.

These two numbers don’t work independently. If you switch to cycling faster, say 30 spm, and you don’t see a drop in the 500 splits, you’re shorting your pull somewhere. Alternatively, if you drop down to 20 spm, you can keep that 500 split, but you need to make every pull count; pull hard. Everyone’s going to have their own cruising speed but aiming for between 24 and 28 spm is considered a good tempo for most rowing — obviously if you’re sprinting this changes. This week’s suggested workout will dive into this in more detail and help you feel it out.

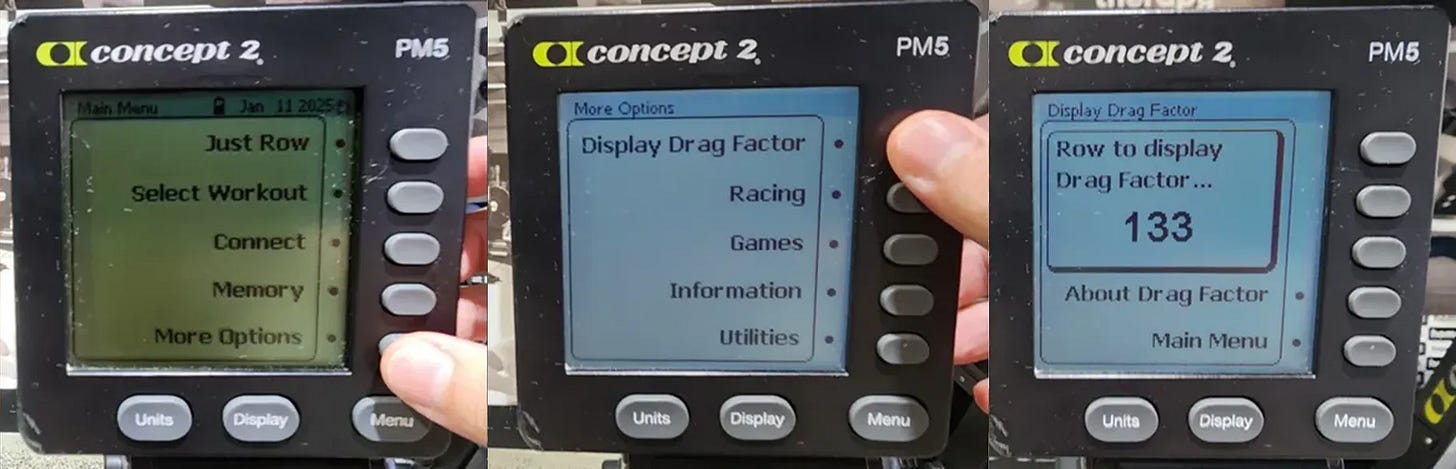

There is also the damper — the wheel on the side of the rower that sticks out over a series of increasing numbers — though we’re not going to adjust it in the way you probably think. The damper can be used to make the row easier or harder, but it’s really good for ‘zeroing’ the rower. Every rower is different, even when they are all the same make and model. How old is the rower? When was the last time someone cleaned it out? These things adjust the overall speed of the rower. If you follow through the menu below, you’ll get to where you can check the drag factor:

Give the rower a few pulls and a number will come up. What you want for your drag factor depends on you, with online sources giving different suggested values for men and women, each at different weights. It doesn’t matter a ton what number you settle on — I usually opt for between 135 and 140 — the point is setting the damper enables you to ensure every rower you get on is giving you consistent and comparable results.

Of course, you don’t have to care about details like this, but I’ve found knowing my PRs helps me drive harder to beat them. So, taking 30 seconds to check the damper is just part of getting started for me these days.

‘What the hell was that?’

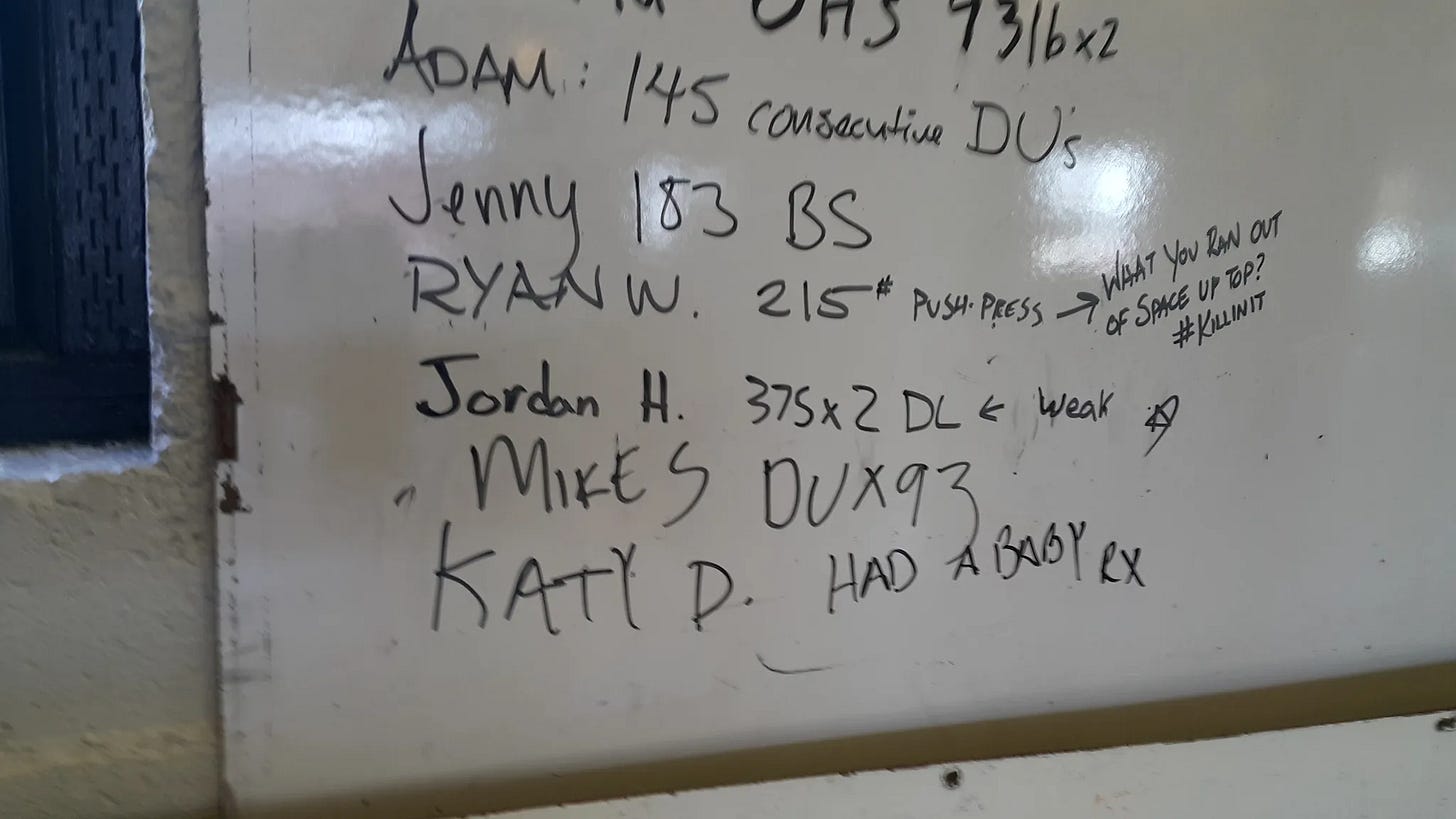

I didn’t discover an assault bike until one morning, right at the end of February 2016. Tacoma Strength had a PR board, which was a white board where you could write any PR you earned. At the end of every month the gym would share the accomplishments on their social media. It was a gimmick, but it worked, and it’s one I stole.

I had managed to get a new PR in one of my Olympic lifts the previous October, only to follow it up with a different lift in November, and a third in December. Suddenly getting a monthly PR had become a ‘thing’ and so I gotten another in January. But February, short month that it is, somehow slipped by me. I came in one morning to discover if I wanted to keep the streak alive, I needed a PR that day.

One of the coaches had recently purchased five of the sadist cycles. I had quietly ignored them until that morning, when suddenly I really needed that PR. There was a whole separate board for the assault bikes, with five different challenges ranging from ‘calories in 3 mins’ to ‘30 mins for distance’. Each challenge had a top three scores for males and females, and I spotted the third place slots were open for both ‘3 mins for calories’ and ‘three-mile time’. I had zero idea how long it would take me to ride three miles on the weird little fan bikes, but I figured it’d be more than three minutes. So, out of ego, I decided to do the three-mile challenge. I was guaranteed to get my name on the board three times, once each for the open slot, and a first time / best time PR.

Somewhere over eight minutes later I fell off the bike on the floor gasping. I laid there and just sweat for a while, trying to get a full breath of air. My lungs burned with lactic acid. ‘What the hell was that?’ I hated it. I loved it. We’ve been soul mates ever since.

The assault bike doesn’t need all the calibration a rower does. Just get on it and go. Going easy gets your heart rate up fairly quickly. Going hard gets it up dramatically. I routinely give unsuspecting soldiers the ‘3 mins for calories’ challenge. When we did it in Baghdad, we had to start telling them not to try walking down the stairs until at least ten minutes after. You don’t get the deadlift gains that a rower gives you on the bike, but the anaerobic tolerance gains have had a huge impact on my fitness. It’s why I typically start three of my five workout session a week on the assault bike.

Both the bike and the rower are machines, which means unlike bumper plates, there’s a lot of difference between different brands. I’m partial to Assault Fitness’ bikes, probably because those are the ones I started on. But the bikes here in Australia are a different brand, which ends up giving me a significantly different score, and there’s no reliable way to zero them out. I’ve found the same with rowers. Concept2 enjoys a similar place of nostalgia for me. But I’ve rowed on every other knock off brand in dozens of hotels around the world.

In the end, as one of my best workout partners liked to remind me, ‘You know what hard work feels like’. Use the digital screens to help your fitness, but don’t let the wrong brand throw off your workout.

Rowers and assault bikes are excellent additions to any workout regimen, whether you’ve just started lifting, or you’ve been a gym rat for years. They get you all the cardio you’ll ever need, help you reach out and ‘count coup’ in that anaerobic space, and they’re practically injury proof.5 If you can’t run anymore, these will be your savior. The only drawback to them is, as machines, they can be hard to come by. What do you do when you’re responsible for more than just yourself? When you have to program a whole squad's gains? We’ll look at some ideas next week.

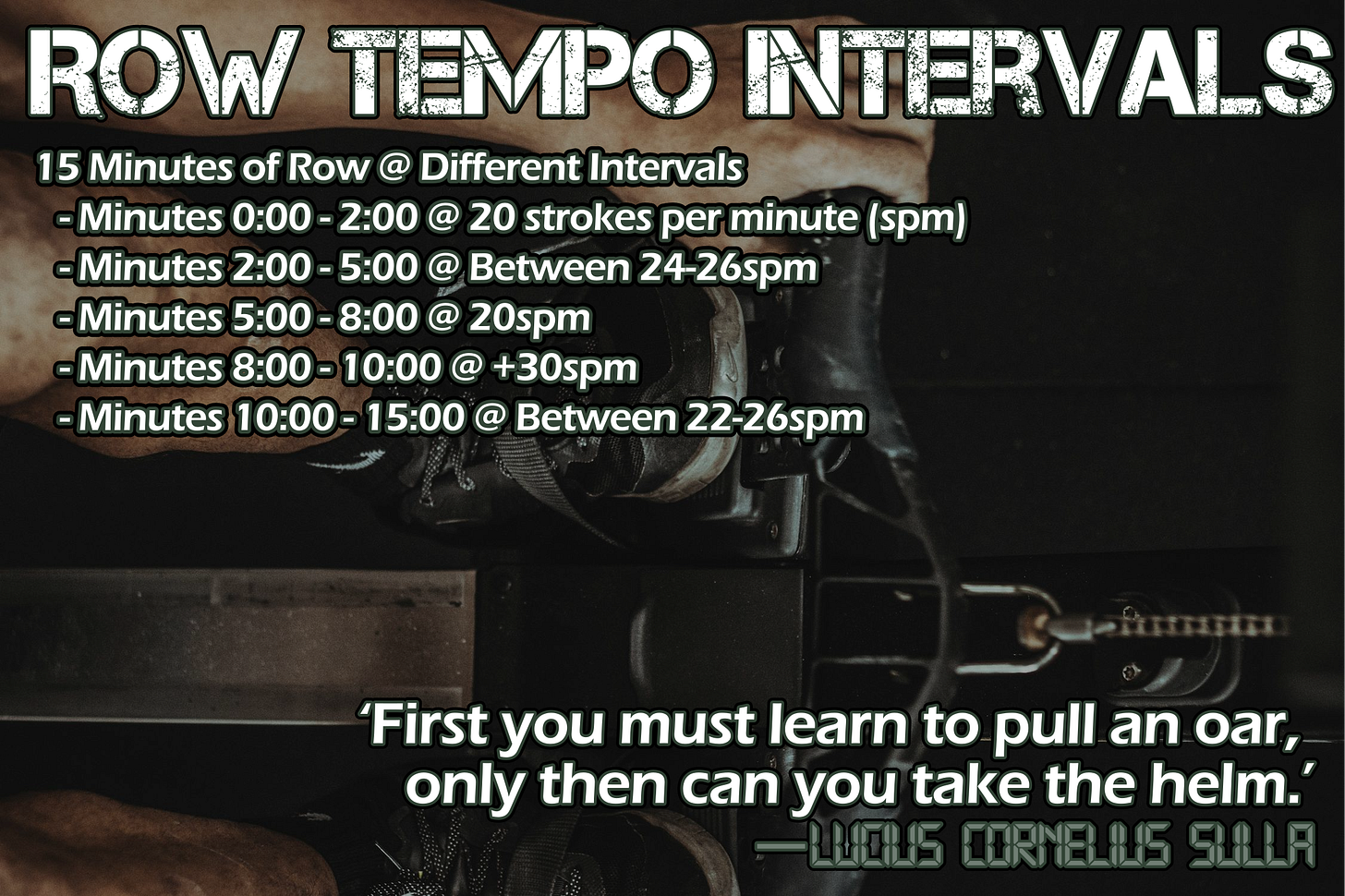

Tempo Row

This set is a great way to learn the rower and refine your technique. It’s fifteen minutes of continuous rowing, but you’re adjusting your strokes per minute at intervals throughout. Your goal is to keep your 500m split as consistent as you can across all 15 minutes. This means 20 spm is going to be hard, deliberate pulls. Feel that deadlift. Meanwhile 30+ is going much more cycling, trading power for speed and rhythm. If you find your 500m split moving more than + or - three seconds, refocus on dialing it in, or accept a slower tempo. Score is total distance rowed in fifteen minutes.

Holistic Health and Fitness. H2F is the Army trying to catch up to SOF’s THOR3 (Tactical Human Optimization Rapid Rehabilitation and Reconditioning). Both are programs focused on improving the mental and physical health of soldiers. Good programs include nutritionists, mental and physical strength coaches, and robust PT resources.

Forward Operating Base. Pronounced like a key-fob, these are generally a combat base large enough to have a chow hall. Smaller than that we called typically them COPs, or combat outposts.

Row machines are called ergs. I don’t know why and never bothered to ask.

It might surprise you, but none of your muscles ‘push’. All they can do is pull. Your body just uses all those tendons, ligaments, bones, and muscles to do some pretty clever physics to make it feel like you pushed something. The human body is a pretty bad ass machine.

Dismounting a moving assault bike can be exciting.

F* that assault bike....especially now that, with a new shoulder, I don't have a reason to ignore that goofy looking pos. I've started IJAM and Tabata sprints since I caught those articles. Making 54 feel even older, haha. Thanks Erik, I hate your guts.

More torture devices than exercise machines. I love and own both. In grad school, on a break from Army fitness, I decided to be wild and try out for the rowing team at the University of Michigan - all on baseline level of Erg fitness in my garage. I eeked out a spot on the team and had a great 7 months rowing with people a decade younger than me. I probably ran 10 total miles in those 7 months where I was in a boat or on a C2 15 hours a week. When I jumped back into running I barely lost a step. Great tools for fitness.