G.2: Nobody’s Week Got Worse With Yoga

Post 4 of 11 in a series on the intersection of data and fitness.

Click here for the rest of the series.

Tell me about your lower back.

The text message from Jason, my battalion PT, stared back at me, impossible to ignore.1 The two of us had just started to try and chase down an intermittent shoulder twinge I was getting, which made diagnosing the issue particularly challenging.

On a whim, I’d taken my GoPro camera to the pool during a recent swim workout to see if I could spot some asymmetry in my stroke. I could not, but I mentioned it to Jason on my way out the door for an overseas trip and he’d jumped at the chance to check it out. He immediately spotted what I’d missed, thus the text.2

I let out a long sigh before responding. That’s a bit of a story.

And it was. I certainly wasn’t the first guy to start lifting weights without any kind of real coaching or supervision. By 2009, as a young captain, I started working out in a gym in Tacoma when one of the coaches pulled out his phone so he could record my deadlift. He made me watch it, more than once, before banning me from deadlifting more than 135 pounds until we fixed my form.

A few years later I was in London and the coach in the gym was making her rounds when she offhandedly told me, ‘You’ve got alligator back’. When I thanked her for the compliment, she looked at me dismissively. ‘That’s the term for overdeveloped back muscles from too many years of shit form’. I’d shrugged in embarrassment. It had certainly sounded a lot cooler.

And then, during that year long deployment to Iraq in 2019, I’d torqued my back on a back squat set. A week off to rest hadn’t made things better, so I went down to the camp aid station where the PA offered me Flexoral. I’d passed, knowing the problem needed real fixing. The PA told me a PT visited our camp every other week and he’d get me in to see her next time she came through.

Walking past her on my way into the clinic the following week felt like being scanned by a TSA check-in. I knew I was in good hands. When she asked me to touch my toes, I explained I never could, even before the injury. I’d always had tight hamstrings, and v-sit reach was the one part of the Presidential Fitness Test I could never do well. She gave me a once over before nailing the diagnosis.

‘Let me guess, you’ve been here, what… two months?’ Check

‘Been getting all kinds of gains?’ Big check!

‘-And you haven’t been doing any mobility work at all?’ …much more reluctant check

She folded me in half a few times and gave me some stretches with direction to follow up with her via email in five days. Then, in closing, she told me, ‘Your hamstrings are fine, by the way. The reason you can’t touch your toes is because of your lower back.’ When I asked her what I could do, she directed me to the camp’s weekly yoga session. It was not a suggestion.

I sent all of that history to Jason in an email and when I got back to the island quickly found myself lying on the PT table in the battalion’s clinic. With one absurdly simple exercise, Jason proceeded to clearly demonstrate what my problem was and give me a pair of new mobility exercises to address it. The movements were designed to activate the muscles in the small of my back. They were a simple but great fix, movements I still do at the start of every session all these years later.

But the more impactful thing Jason did was get me to program my flexibility and mobility with the same dedication I applied to my planning my workouts. Heretofore I'd plan to do some stretching after my warm-up, and nine times out of ten, never get around to it because of the rush to get to the desk in the morning.

Emails can wait. Mobility cannot.

‘An Ounce of Prevention…’

Mobility and flexibility are the first thing I do after a brisk three-minute warm up. I do different targeted movements every session, and just like my WoD, I make sure I make them up if I miss a day. One hack I use is each individual movement gets its own check box in my app where I keep my log. This means every time I complete one, I get that sweet little dopamine hit to the brain which helps rewire the feedback loop. That hit builds habits. Mobility habits might be the most beneficial ones I have.

This is because injury prevention is a huge part of both fitness and readiness. If you’re hurt, you aren’t ready. You also can’t keep getting your gains. Even maintains become a challenge. And so, your fitness suffers.

For most of us, it wasn’t getting older that made us weaker. We got weaker because somewhere along the way we got hurt. As you get older the recovery time from injuries increases. Avoiding unnecessary injuries goes from just being smart to being essential if you want to maintain your readiness.

Since I started both deliberately planning and meticulously doing my mobility work, I have avoided almost all injuries. This has enabled me to build and maintain possibly the highest level of readiness I’ve had since I was a captain.

I’m certainly more flexible than I was as a decade and a half ago. After just three weeks of yoga back in Iraq, I was able to reach down and touch my toes for the first time in my adult life. I kept going to the weekly yoga sessions until first ballistic missiles and later COVID shut them down.3 It’s not something I do without instruction, so finding a class can be a challenge every time I move. But it’s been an unambiguous good in my life. I’ve never once regretted a yoga session.

And in addition to improving my flexibility and core strength, yoga also refocused me on my breathing. This is because when I started, I was completely incapable of synching my breathing with the movements. I was typically panting within the first fifteen minutes; breathing in and out smoothly and solely through my nose wasn’t even in the cards.

Learning How To Breathe

A couple years later two friends suggested I check out James Nestor’s Breath. The book explains just how impactful our breathing is to our overall health. Nestor’s research found, ‘The greatest indicator of life span wasn’t genetics, diet, or the amount of daily exercise, as many had suspected. It was lung capacity.’

I’m skeptical of ‘superfoods’ and other fitness crazes, in particular because they are all too often based on very limited data. Aaron Carroll has an excellent YouTube channel ‘Healthcare Triage’ that points out how many nutritional studies are data poor, and I highly recommend his book ‘The Bad Food Bible’ as a great primer on how to read food and health news.

Thus, while I was intrigued by Nestor’s claims in Breath, I still had a healthy amount of skepticism. However, he wasn’t selling anything. I didn’t have to buy some new product or supplement. All I had to do to try it out was breathe a little differently. So, I gave it a shot. I started focusing on my breathing during my workouts and challenging myself to see how long I could sustain nasal only breathing.4

The short answer was not long. Some of this is biomechanical. Mouth breathing allows for more oxygen to get rapidly to muscles. It also enables some heat exchange, so when your heart rate reaches certain levels, you’ll naturally start panting in much the same way other mammals do.

Focusing on nasal breathing helps me in two ways. First, it helps me informally measure my heart rate.5 If I can’t sustain nasal breathing during a set where I’m prioritizing the quality of movement, like Turkish get ups, I slow down or reduce the weight.

Second, I use nasal breathing to help recover between sets. As I wrote about last week, our bodies triage oxygen to where it thinks the greatest need is. This means under stress muscles can come in first ahead of higher-order brain functions. Reducing your heart rate can sometimes be the only thing you can do to stop being stupid. Lowering your heart rate typically requires you to stop doing things; preferably stop doing just about everything. Breathing is in fact one of the few things you can actively do to help.

As an example, one of my recurring workouts is Bear Complex. I start every fortnight of programming with Bear. It’s a cycle of five continuous movements - power clean, front squat, push press, back squat, and push press. I do that five-lift cycle seven consecutive times without putting the weight down. And then I do that set of seven reps five times each.

Bear doesn’t need to be heavy to take a toll. I typically use just barely over half my body weight. By each seventh consecutive rep I’m typically gasping. I do each of the five rounds on three minutes. It only takes me about a minute to get through the seven reps. This leaves me about two minutes to reduce my heart rate back to a cardio rate before I’m picking up the weight again. Intentional breathing is what gets me there.

This style of work — mainlining my heart rate only to stop, breath through recovery, just to start up again — is the bulk of what I do for my readiness. It is the reason I’ve consistently been able to pass any fitness test the army or life has given me. It answers perfectly the demands of #2, 4, & 5 from the army’s demands for operational fitness. Throw in some decent weight and you’re checking all six boxes.

Of course, this also means you need to do something we all hate to do: embrace failure. More on that next week.

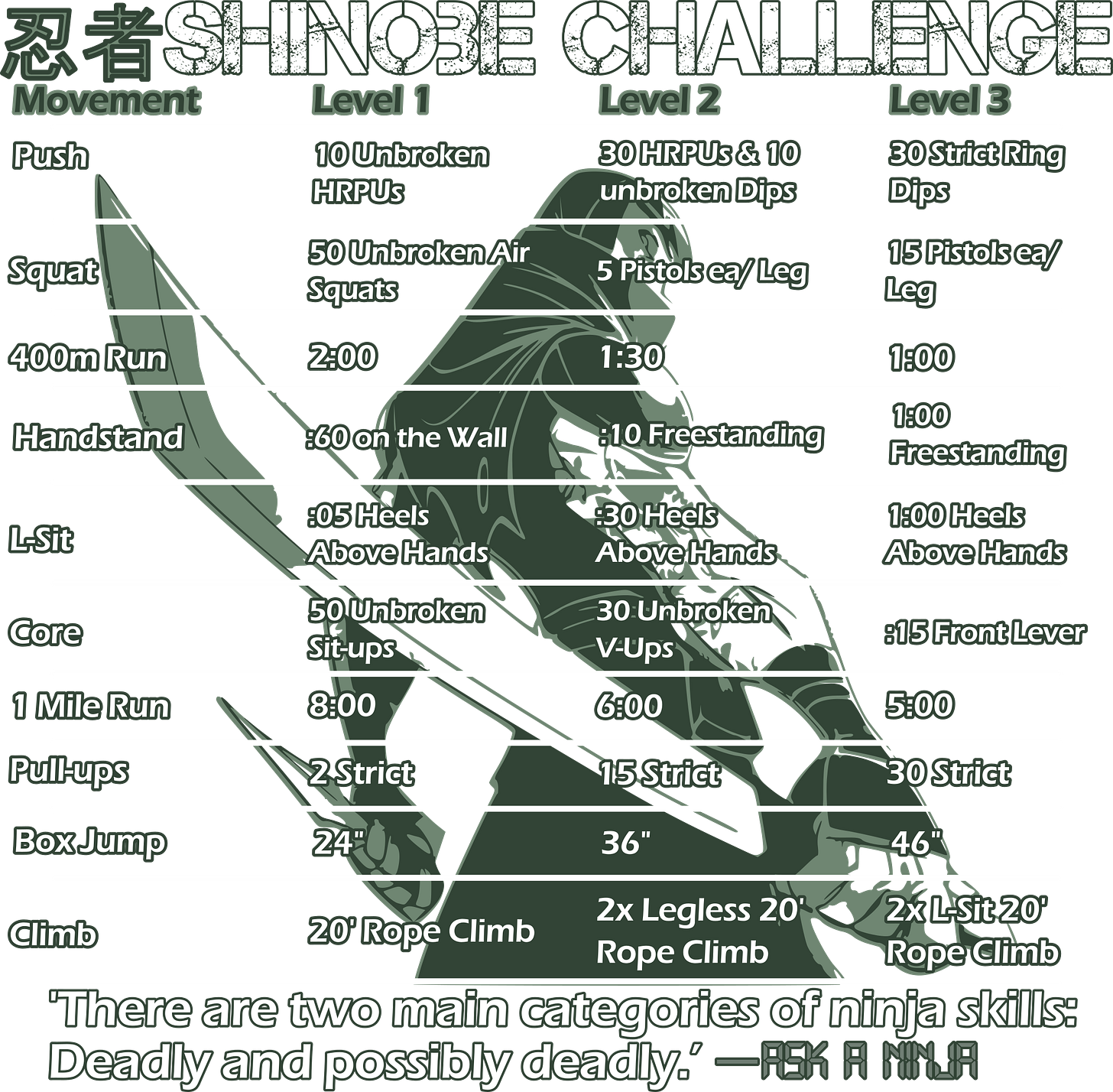

忍者 Shinobe Challenge

Like last week’s workout, this one comes from my time at Tacoma Strength with Morgan Blackmore and Leon Aldrich, who established the standards which these are stolen from.

忍者 (Shinobe, more commonly known as ninja) is biased toward agility skills. Level 1 is your baseline: If you can’t complete any skill at Level 1, those are holes in your swing. Except unlike last week’s Hoplite Challenge if there’s a problem with your agility, that’s a serious problem you need to focus on before you focus on your strength — see ‘alligator back’ above. Get with your PT and strength coach and develop a plan to get you moving right. Doing all the Level 1 standards in a single session is a light workout on its own, and something also I do every October.

Once you can achieve all of the skills at Level 1, start trying to tackle Level 2 challenges one at a time. These fit well at the start or end of a day’s session. If you can manage to achieve all of Level 2, you have a very solid level of agility and mobility readiness.

Level 3s are real challenges, and getting any of them is something to be proud of. Achieve more than half and you need to get yourself to an audition for American Ninja Warrior.

Unhelpfully the army abbreviates fitness, or ‘physical training’ as ‘PT’. Except army PT sucks and is generally reviled across most formations. This series is an attempt to address some of the root causes of that, and we’ll start with the name. For the last five years I have referred to fitness training as ‘gains’, because gains are definitionally a good thing. And they are personal, because they are relative to you. You gain from where you started. Gains are non-transferable, though they can and should be shared. For the purposes of this series, the initialism ‘PT’ will only be used to refer to ‘physical therapy’.

I’ve never had a bad PT, but Jason was a particularly exceptional one. Much of this post is owed to him helping me change the way I approach maintenance and mobility in my fitness paradigm.

While this post is focused on physical fitness, yoga has also been exceptionally good for my mental health. When I started, I found the first ten minutes of yoga to be excruciating. Not because of the stretching — well not just the stretching. Yoga was exhausting because it was. so. fucking. slow. But that forced time to slow down, to stop flitting from email to email, meeting to meeting, has been great for helping me destress and reprioritize my focus.

I also tried out Nestor’s tape trick for nasal breathing at night. This took some getting used to, but I’m actually a huge fan. I no longer keep my wife up with snoring, and I’m avoiding a CPAP machine. All at a price of what can’t be more than a few pennies a night. I wake up feeling like I’ve done hours of slow deliberate breathing, because, well I have.

I’m not opposed to wearables. They can be a great data source. But I haven’t needed them or used them much. I don’t wear rings while working out, so Oura’s out. I have tried out a watch, but only really wore it while cycling, before I smashed it doing kettlebell snatches.