Quantity versus quality. These are often presented as a binary choice, when in reality it’s really more of a spectrum. It only resolves down into a binary when you impose a requirement, a standard. The army is trying to do just that with the new AFT combat MOS standards. It remains to be seen how committed they are to it. Based off the language in in HQDA EXORD 218-25, they seem pretty serious.

This is a long post, but I’ve put in short cuts for those in a hurry. I’ve written a quick summary of the changes of fitness standards, as well as a longer detailed breakdown of how each event’s scales have adjusted. Up front I’ll quickly cover the change to how the army is administering the new AFT. I will also lay out where I see the most likely risks in implementation. As I did with my ‘Where Data Meets Gains’ series, I’ve also included a suggested workout, ‘Peanut’, at the end to help those who need to get ready. I can’t think of a better workout to get yourself ready for the new standards, so I highly recommend you check it out.

What Changed?

First up, the AFT has new scores for all MOSs, but the biggest change is we now have two tiers: combat MOSs and non-combat MOSs (which I’ll also refer to as gen-pop).

The AFT combat standard applies to specific combat AOC/MOS... It is sex-neutral and age-normed, requiring a minimum score of 60 points per event and an overall minimum score of 350 points.

The combat MOSs are:

11A, 11B, 11C, 11Z, (Infantry)

12A, 12B (Combat Engineers)

13A, 13F (Field Artillery officers and Fire Support Specialists, but not gun bunnies, FDCs, MLRS, nor {of note} their SGMs)

18A, 180A, 18B, 18C, 18D, 18E, 18F, 18Z (Special Forces - Green Berets have the only Warrant Officers subject to the combat MOS AFT standard)

19A, 19C, 19D, 19K, & 19Z (Tankers)

Starting in June, the army is going to counsel every soldier on the new standards. Those in combat MOSs need to meet the new AFT 350 minimum. That’s either 70 points in each event, or you need to make up points for any event where you dip down to 60 points. Those whose on-record ACFT score doesn’t meet the new standard will be counseled separately. They will also be given a chance to retake a ‘first assessment’ AFT before August. Those who pass can go on about their day, safe in the knowledge they met the standard.

However, if a solider does not get a 350+, they will be flagged in the personnel system and have until December to improve or reclass. The specifics of reclassing get complicated and I’m not going to cover them here. Get ahold of your career counselor or HRC rep if you have specific questions. Soldiers may take an optional AFT in December if they want to stay in their MOS; however, if they fail, voluntary reclassing won’t be an option after. The army is looking for soldiers in 17 specific MOSs — see the table in the footnotes.1 Your career counselor / HRC branch rep is the best source for what’s available to you.

One carve out is for those combat MOS officers MAJ to COL and SF Warrants who do not pass. They ‘will remain in branch and serve in positions not associated with combat’. I haven’t found specifics for which positions those are, but command is definitely not one of them. This rule may not apply to Green Berets, since USASOC recently issued a directive revoking SF Tabs for those Green Berets who fail to pass the ACFT and meet height and weight standards. There is also some language on how to manage profiles, so if you have a physical profile, get with your medical leadership on how to proceed.

Why the Change?

This part is key, so I’m going to quote the directive a couple times:

The army analyzed existing ACFT performance data (over 800,000 tests) to identify ways to raise standards for specific combat areas of concentration (AOC), military occupational specialties (MOS), and the army as a whole. Further insights were gained through a pilot program in May and June 2024, where approximately 45,000 soldiers took a practice ACFT with elevated standards. This analysis informed army senior leaders' decision to increase physical fitness standards army wide.2

The reason I think this is key is because the army botched this in 2018 with the ACFT roll-out, when there was no clear communication plan executed. The directive clearly orders all leaders to provide ‘clear and prompt communication of the new AFT standards and necessary soldier actions to achieve them’.

The army seems to understand how bad they rolled out the ACFT, and the directive even sees the need to reach out beyond just the command channels.

Along with podcasts like “From The Green Notebook” and “MOP and MOEs.” Social media influencers, both internal and external, should be included in communication efforts.

Anyone looking to amplify the messaging is directed to use ‘#AFTReady2025’.

The reason for the AFT change for all soldiers is:

‘The five-event AFT is designed to increase warfighting readiness, reduce injury risk, and enhance the physical performance of the force.’

Those who read my summary of the RAND study can see why the army ditched the overhead ball throw, since it was the one event associated with higher injury risk. The change to combat MOS standards was assessed in that same study.

‘The AFT, informed by RAND analysis, is designed to improve readiness, enhance lethality, and reinforce the warrior ethos.’

The one thing the army hasn’t communicated is why these combat standards are ‘age normed’. If the rigors of combat don’t discriminate on gender, then they damn well don’t take age into account either. The army has a reason, and they should lay it out.

I think the AFT change is a welcome one. But I also think our army culture also needs to change. We need to accept and communicate that being the fittest doesn’t automatically mean being smartest or a best leader. For most of my career, we bred officers and senior NCOs who thought run times were the best yardstick for leadership. I personally served under two commanders who overtly used running to assess leadership talent. Both are now felons.

Combat MOSs are getting a higher physical requirement because those jobs have higher physical demands. But that doesn’t make a non-combat soldier in any way inferior. We have different jobs and when it comes to the highest levels of leadership, strategic thinking matters more than your deadlift. We already tend to breed short-sighted tactical corgis in the combat MOSs. Making them yoked won’t make them any better at strategy.

Watch the Leaders

The reason I’ve taken time to bang the drum on the messaging is because leaders botched it so badly last time. The ACFT has been out for six years and yet soldiers in last year’s RAND study were still found to be unfamiliar with the movements.

Leaders failed. They failed to make the change in large part because those same leaders had the most to ‘lose’ in the change from the APFT to the ACFT. You can see this clearly in the ACFT standards, which were adjusted in 2023 from the original 2019 ones based off thousands of soldiers' results. There is a sharp drop off in the 37+ crowd who opted to not adapt to the new fitness test, weighted down heavily by senior NCOs and officers who didn’t want to learn a new form of fitness.

This time specifically those senior leaders in combat MOSs are the ones whose standards have been raised. I detail the specifics below, but the ages that see the biggest increase in combat MOS standards are the 37-56 year old cohort. We need to pay attention because the people with the most power in the army are also the ones most likely to be impacted by the change.

The directive takes aim directly at leadership:

Effective 1 January 2026, promotable combat branch warrant officers and officers, in the grade of WO1 to CW5, MAJ to COL, who do not achieve a qualifying AFT score will be flagged and subsequently withheld from promotion. Effective 1 January 2026, officers must meet the combat standard to be eligible for command.

The new standards are not excessive and I think most combat MOS soldiers are already exceeding them. I recalculated all my previous ACFT scores and ended up with an average of less than a single point difference, principally because I’d adopted the plateau mindset for the deadlift I decried last week.

But I do know some fellow Green Beret LTCs, COLs, and SGMs / CSMs who will struggle to meet the new 350 standard. Some of them are in or about to take command. If this is true for SF, then it is certainly true for the other combat MOSs. And we can identify those leaders at risk right now. Because the army already has all our CAP / SMAP ACFT scores.

The directive doesn’t just apply to command teams:

Soldiers at PME about to graduate this month who do not meet the standard will have a graduation waiver that states as such.

For all those soldiers like me at the Army War College or equivalent, or those at ILE and the Sergeants Major Academy, the army already has our ACFT on file. The army already knows if we’re meeting the AFT standard.

Effective 1 January 2026, promotable combat branch officers, in the grade of 2LT to CPT, who do not achieve a qualifying AFT score will be flagged and subsequently withheld from promotion. Effective 1 January 2026, promotable combat branch warrant officers and officers, in the grade of WO1 to CW5, MAJ to COL, who do not achieve a qualifying aft score will be flagged and subsequently withheld from promotion.

General officers, who no longer have branches, are likely not going to be impacted. But by the letter of the policy, CSMs who wish to retain their MOS must meet the standard.

An overdue reckoning

I’m sure the bulk of the media attention will be focused on the impact the new AFT combat standard will have on females. But that’s not where I’ll be watching. Because the real question isn’t how many females can meet the combat MOS standard. It’s how many males can?

I have never had the data, but I long wondered if doubts about that question were what really drove some of the resistance to letting females try out for combat arms. After all, if you firmly believed that females could never meet or exceed the physical standards, then you could just sit back behind that impervious wall of standards.

Instead, for years we saw a lot of male soldiers decry even letting females attempt. Some people were so committed to the idea females couldn’t meet the standard that when women did meet and exceed the standard, they refused to accept it, claiming ‘they changed the standard’.

There are a few select units that can hold incredibly high standards and they have one trait in common: they are very small. As an example, the Ranger Regiment still insists all their officers and NCOs have a ranger tab, even their support soldiers. They struggle at times to fill low density MOSs, but when you only need four Ranger qualified mess NCOs, you might be able to find them across the entire army.

Green Berets will often whinge about how the SF Regiment doesn’t hold a similar high standard for our support MOSs. But the math breaks down when you realize there are five times as many SF groups as Rangers. When I was a battalion XO, I found I needed a property book officer a lot more than I needed an airborne property book officer.3

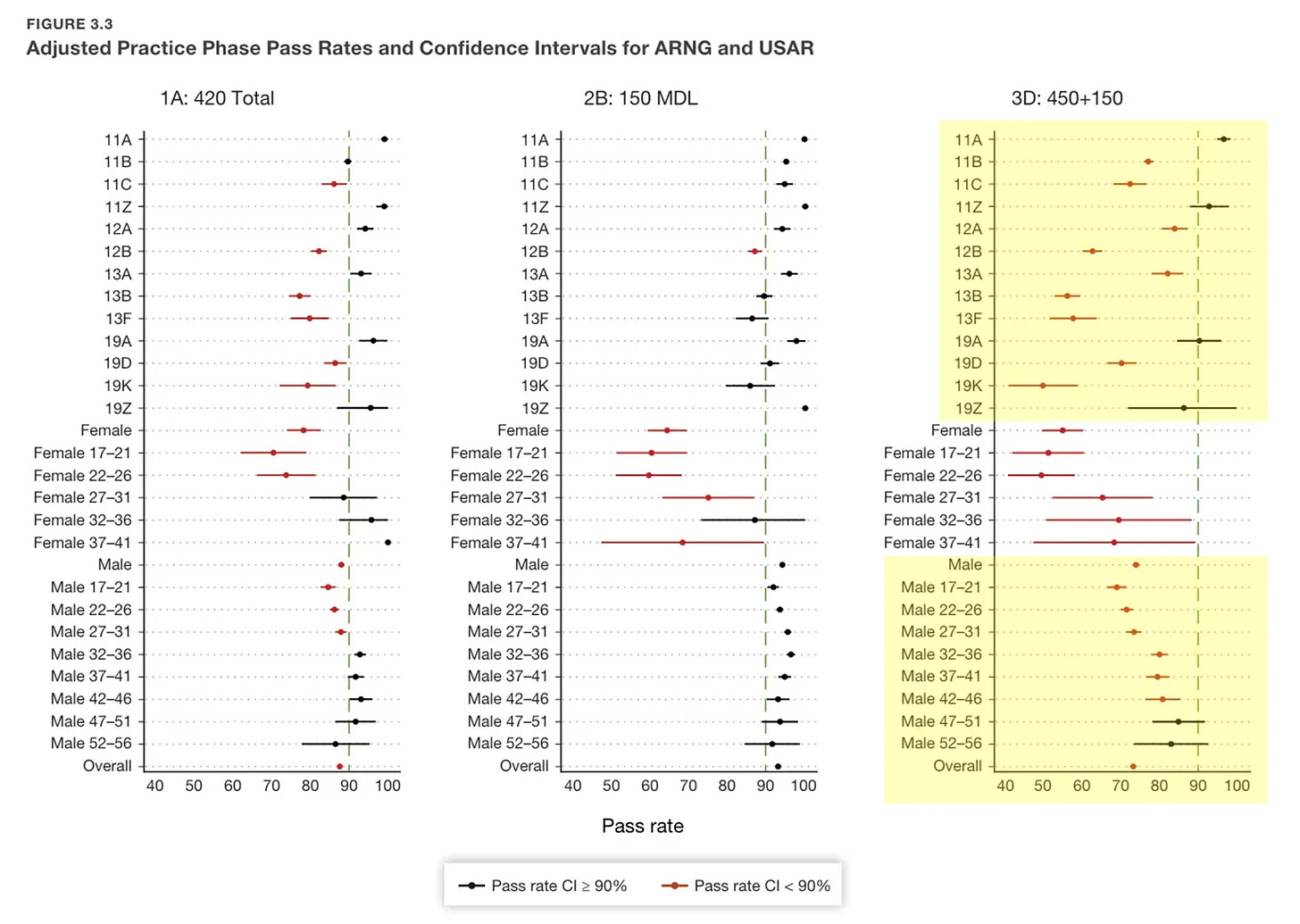

But the infantry isn’t small. Despite their fewer numbers, the tanker corps is pretty big too.4 When you need thousands of infantry to fill the squads, the tension between quality and quantity starts to grow. In my first infantry battalion, there were a lot of infantryman who could not pass the new 70 minimums for today’s AFT. If you deny females for not meeting the standard, you have to potentially cut all of those males who couldn’t perform either. There are likely a lot of them across the active army and in particular, the national guard.

I think that’s a big part of why people didn’t want to let women show they could exceed the standards. Well, women spent the last decade doing exactly that. Now a lot of fragile male egos are about to find themselves having to put up or shut up.

What’s the risk?

I’m not arguing that the army is wrong to set a higher standard for soldiers’ fitness — I have already written about my support for higher combat MOS standards. But there will be an inevitable tension when combat MOS soldiers don’t meet the new standard.

Because one advantage of the AFT and ACFT over the APFT is you can’t just pencil whip it anymore. It used to be easy to just say ‘Oh Gary and Rick gave me one the other day. I got a 277’.5 ACFTs and AFTs take logistics. People see you take them and they know when you didn’t.

I have also served in units that tried to navigate the tension between a high standard and manning. Leadership is harder in these units, because there’s increased pressure to lie. Numbers get fudged. When the people with the most power are the ones with the most to lose, there’s an even greater likelihood of undue influence. That’s when a commander or sergeant major reaches down to change a score to protect their career.

And in the worst cases, the culture of the unit comes to condone things like steroid use. Soldiers do not need to use steroids to meet the combat minimums. Indeed, no challenge the army has given me in 22 years warranted using steroids. I can say that until I’m blue in the face, but I think the army needs to have a plan to test randomly for steroid use among combat arms units to prevent this culture from infesting our formations.

AFT Cliff Notes:

The thorough dive is in supplemental post, but here’s the quick facts on the AFT you need to know. I’m not going to focus in on the max end of the scale. This is in part because, as I detailed above, the new standards don’t move the max needle much. I still don’t think the army should use max standards, but I’ll have to keep that fight going for another day. I’m also not going to cover the 57-62+ crowd because, though I don’t know how many active duty combat MOS soldiers there are over 56, I’m fairly confident none of them read my substack.

As quoted above, soldiers can earn as few as 60 points in any event as long as their total score is at least 350, for an average of 70 in each. This means if you miss five points on the deadlift, you have to make those five points up somewhere else. That said, the new 70 point standards, while higher than the ACFT, should be very achievable for a combat arms solider.

The Combat Standards

The required deadlifts are between 136-167% heavier for soldiers who only earned the previous 60 point minimums. These jumps depend on age and gender, but the new passing standard is 190 pounds for everyone but 17-21 year olds, who have to lift 200.

Percentage wise, HRPUs minimums saw the biggest increase, But the old standard of just 10 push-ups was possibly the weakest requirement in the whole ACFT. Since the old scale was gender neutral, both sexes need to do between 18 more reps for 17-21 year olds, down to just 12 more for those ages 47-51.

For combat MOS soldiers who were only passing the ACFT at 60 points, I think the Sprint Drag Carry is going to be the most challenging obstacle. The new combat standards are on average :26 seconds faster for men and 1:25 faster for women. Given how short the SDC is, this will mean those soldiers will need to complete the test in just 59-86% of their previous time.

The plank, like the HRPU, was also already gender neutral. It also got marginally harder. Combat soldiers need to now hold out for an additional :32 seconds on average.

The run standards got faster across both ages and genders. Soldiers 22-31 will need to run a 9:11 pace per mile, while those younger 17-21 year olds get an extra :07 seconds to pass. Combat soldiers 32 and over need to maintain a 9:15 pace per mile, which descends to a 10:10 pace as they age up to 52. These run standards are between 11-12% faster than the old ACFT minimums.

You can download a printable one-pager of all the above charts here.

The AFT Gen-pop Minimums.

The AFT score changes weren’t just for combat MOS soldiers. Non-combat MOSs saw their standards increase in three of the five events. There were no changes to the minimums for the sprint drag carry nor the plank.

Males under 32 saw their deadlift minimum increase by 10 pounds. Everyone else’s remained the same. Males aged 17-21 will need to do five more HRPUs, descending to just one more when they turn 47. Females will need to do a single additional HRPU from ages 17-36. As for the run, all soldiers under 57 will now face faster standards.

The biggest change is males ages 22-31, who need to run 2:15 seconds faster. For females the cut is smaller, only about a :30 seconds for those under 52. Regardless, soldiers who can manage 10 minute miles will have little trouble passing.

We’ve got six months

These new standards are not insurmountable. The AFT gen-pop minimums are very achievable and even the combat minimums aren’t impressive feats of strength for those who do these jobs every day.

What is key is we as leaders help our soldiers get there. Not everyone in your formation is ready today. But we’ve got till the end of the year to get them there. That means we as leaders need to step up. We need to not only explain why and the how of the change, but we need to lead our formations in a new style of fitness.

Fitness is not just an NCO job. In fact many of the army’s senior NCOs are the product of decades of training that only focused on ‘push-up, sit-up, run’. They may not know how to train for this new standard of readiness. The challenge is on all of us. We can do this. But we need all leaders, officers and NCOs to lead. It was leaders who failed us last time. Don’t be one of them this time.

Welcome to the new fitness standard: ready. If you’re already there, take the next six months to get someone else ready. If you’re not ready, go read, go learn, and go train. Get your formations ready. #AFTReady2025

Peanut

Ronnie Coleman is a bodybuilder with a knack for great quotes, proof that being a strong ranger and a smart ranger is no more a binary choice than quality versus quantity. The WoD ‘Peanut’ is named after him.

Back in 2019, when a pending combat deployment to Iraq forced me to start programming my own workouts, this was one of the first workouts I did. It was the first day of May and already humid in North Carolina as I stood there in the outdoor prison gym glaring at the barbell in front of me. I didn’t want to do the workout, anymore than I wanted to do my own programming. I’d been spoiled for over a decade by going to great gyms with great coaches who, in addition to teaching me how to lift, train, and recover had also programmed my workouts for me.

Now it was my job. I’d seen Ronnie’s quote, ‘Ain’t nothin’ to it, but to do it’ emblazoned on the wall of more than one gym over the years, and it came back to me there in that moment. And so I started.

‘Peanut’ has been one of my regular WoDs ever since. It’s a good workout for anyone, but if you’re a combat arms soldier who’s sweating the new 70 point minimums, I can’t think of a better WoD to get you there. You’ll get plenty of deadlifts and the burpees will improve both your HRPU and planks. The whole set is a cardio gas, so it’ll improve your VO2Max while those bar facing burpee-over-the-bars are going to help your agility for the SDC. If you add this once a month into a decent workout regimen, I’m confident you’ll get to where you need to be by the 01 January 2026 suspense.

Peanut has a fair amount of deadlift reps, so focus on making each deadlift solid. Don’t rush into a back injury because your form went to shit. If you can’t deadlift 225 pounds yet, then just scale the weight back. Start out with what you can do and work your way up each month. The rounds are set as fractions of bodyweight — 1/2, 3/4, 1:1, and 5/4 — so use that as an aim point.

The reps come down as the weight goes up, and by the end you’ll have done way more than the three-rep 200 pounds you’re required. Three minutes is actually a fair amount of rest between each couplet — deadlift-burpees, deadlift-burpees, then rest. Focus on getting your heartrate and breathing under control in between. This will also help you train for the shorter transition between the AFT’s events.

I have converted this from GENTEXT because, unlike the army, I don’t hate you.

Some would say quantity trumped quality there; but in reality the quality I needed was his knowledge, not his ability to do something no SF group has done in our history.

A trick I learned to spot a fake PT score was it ended in 7. I’m not saying every 7 was fake, but when soldiers made up an APFT score — and they didn’t just write ‘300’ — it almost always ended in 7. The reason is because it sounds more real. Round numbers sound suspect, ruling out 0s and 5s. For no better reason odd numbers sound more real than even. So you’re left with 1, 3, 7, and 9. 9 Ironically looks like you just missed a better score — ‘Could’ve been a 280’. Meanwhile, 1 looks like you barely did anything more. So you’re left with 3 or 7, of which 7 is better.

Look for a disproportionate number of 7s in your units’ fitness tests.

Sir, one quick question unrelated to the points hammered home in the article. You said “And in the worst cases, the culture of the unit comes to condone things like steroid use.”

I assume you have the experience and/or knowledge to label that scenario as “the worst case” like you did. Admittedly, I have a lot of scar tissue with this issue myself.

This is probably another example of me living in a bubble, but do you think that steroid use in our formations makes the list of our top 5 concerns?

Great breakdown - I wonder about another side effect that may occur. Combat MOS Soldiers intentionally score below the Combat MOS AFT standard but still pass in order to force a reclass.