The famously data driven RAND drops a report on the ACFT right before Christmas? That’s the gift I didn’t even think to put on my list. Full disclosure, this post was not on the original plan and is one of the longer ones. I’ve tried to break up the text with lots of charts the RAND team graciously made. It’s too long for email, so you’ll need to read this one on Substack.

For those who aren’t in the army, the ACFT is an attempt by the army to use data to determine our fitness standards. The original grading rubric was not set on age or gender, but on the requirements for the job. Some jobs had to meet the minimum ‘gold standard’, while close combat jobs had to meet higher ‘silver’ and ‘black’ ones.1 This was not without controversy and, after much clamor, in 2021 the army opted instead for the more familiar age and gender stratified option. The grading scales were based off the diagnostic data of thousands of soldiers taking the ACFT data over a year.2

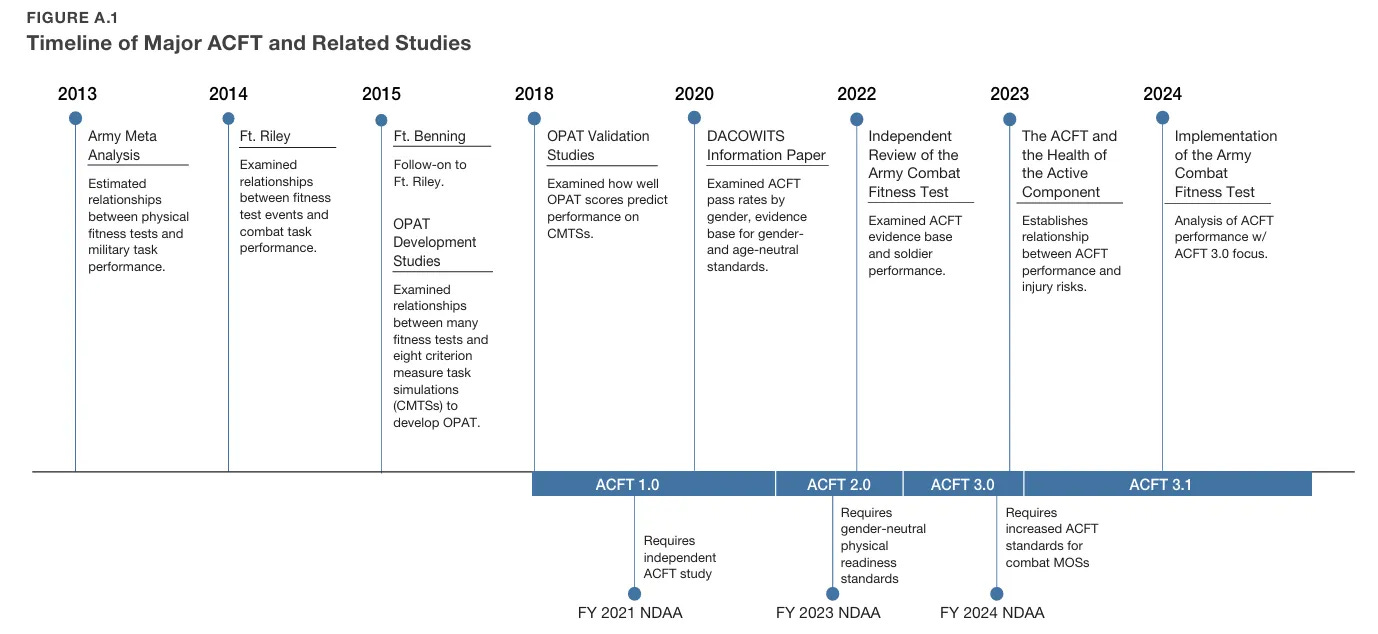

Last month’s RAND study was drawn up to prepare the Army to respond to a line in the 2024 NDAA (2024 National Defense Authorization Act). Specifically, section 577:

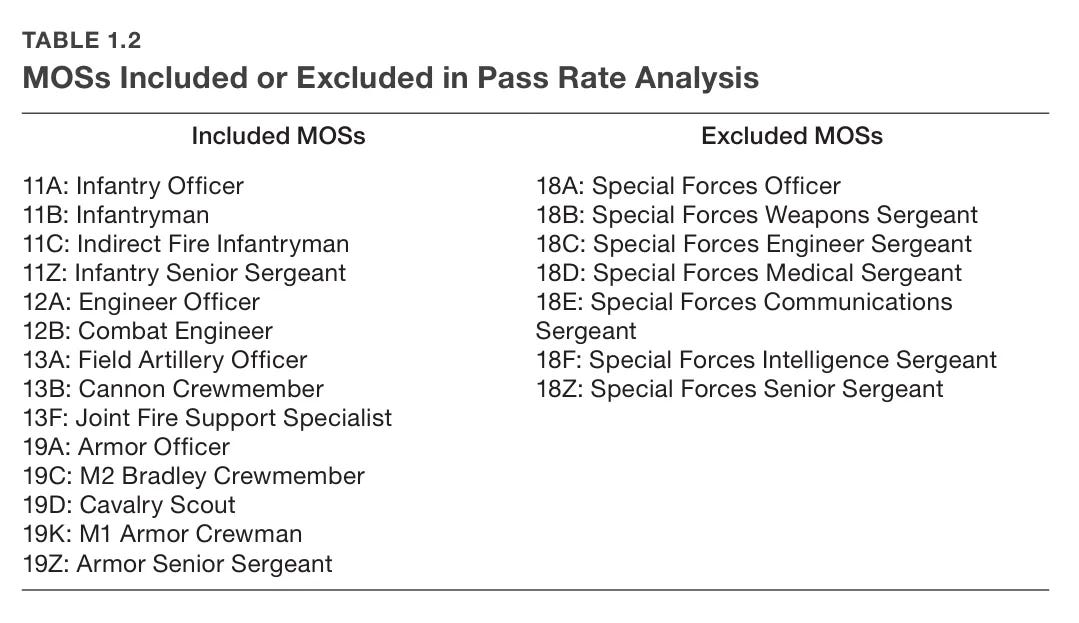

‘(a) Implementation.--Not later than 18 months after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the Army shall implement increased minimum fitness standards as part of the Army Combat Fitness Test for all soldiers of the following military occupational specialties or areas of concentration: (1) 11A. (2) 11B. (3) 11C. (4) 11Z. (5) 12A. (6) 12B. (7) 13A. (8) 13F. (9) 18A. (10) 18B. (11) 18C. (12) 18D. (13) 18E. (14) 18F. (15) 18Z. (16) 19A. (17) 19C. (18) 19D. (19) 19K. (20) 19Z. (b) Briefing.--Not later than 365 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the Army provide a briefing to the Committees on Armed Services of the Senate and House of Representatives describing the methodology used to establish standards under subsection (a). (Public Law 118-31, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2024, December 22, 2023.’

RAND added 13B to that list, but for those unfamiliar with Army MOSs, here’s what each of those jobs are:

The study examined the potential impacts of increased minimum standards for those MOSs. I’ve got lots of thoughts, to include about what jobs did and didn’t make the list. But first, what did RAND find?

Here’s a handful of topline takeaways:

Passing any of the six ACFT events is associated with reduced injury risks. Higher performance levels are associated with lower injury risk for all events except the Standing Power Throw.

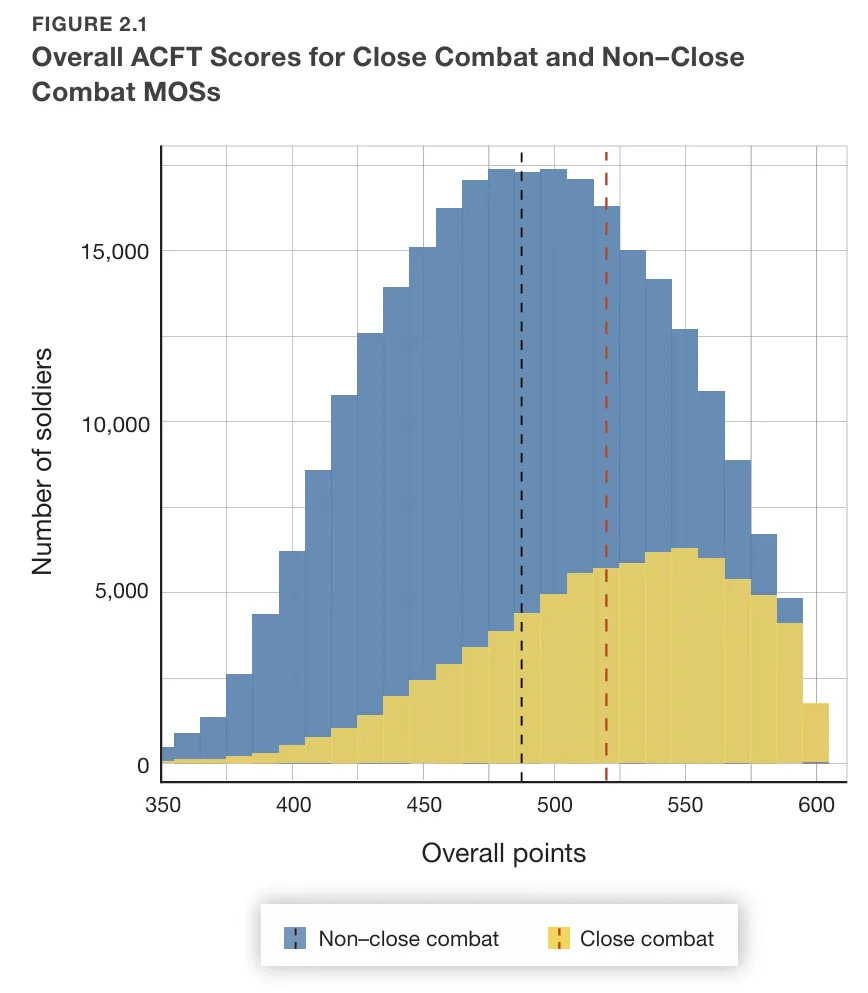

Overall ACFT scores for soldiers in close combat MOSs are, on average, 6.5% higher — appx 40 points — than those for soldiers in the general-purpose force.

There is strong evidence to support a specific, higher deadlift minimum standard for close combat MOSs based on combat task performance.

The National Guard is disproportionately not ready. The report lumps National Guard and Reserves into a single category, but only 502 of the 47,744 soldiers tested (1.1%) were reservists, so damming the reserves seems a bit harsh. Given the tested minimums were well below the level of fitness we expect from close combat forces, this National Guard performance is disconcerting.

Soldiers’ performance improves with experience. RAND saw performance improvement in all six ACFT events during their assessment — particularly among soldiers who did not meet the standard in their previous ACFT attempts. What’s not as clear is why six years after the ACFT was announced, soldiers are still lacking in experience.

I’ll take some time to address each in turn, and close out with some final thoughts.

That Stupid Ball Throw

Despite the persistent narrative that the ACFT, and in particular the deadlift, would increase injuries across the army, RAND found the opposite in all but one case. Soldiers who excelled at the deadlift, push-ups, the sprint drag carry, planks, and even the run all reported lower than average injuries. This is a compelling finding given that RAND reported, ‘… over the course of 2021, over half of all U.S. Army soldiers sustained an injury, three-quarters of which were overuse injuries’ [emphasis added]. The standing power throw was the one exception, ‘…for which injury rates were higher among soldiers with higher performances.’ Do you want to know why?

Because nobody power yeets a weight over their goddamn head! Go watch a video of a caber toss or a hammer throw. The movement for the standing power throw bears no resemblance to any task a soldier actually does. I’ve heard it billed as simulating helping another soldier over a wall. Nope. That is 100% not how you help anyone over an obstacle; not if that person is wearing kit and especially not if there is any possible threat on the other side. The army also claimed the standing power throw simulated a grenade throw. If that’s how you throw your grenades, you can kindly throw them far away from me.

What the standing power throw is actually trying to do is measure your explosive power, as opposed to the static strength of the deadlift. We should be doing cleans, but with everyone already up in arms about the deadlift as a source of injuries, no one was going to sign off teaching people how to do a proper clean. However, thanks to a bunch of majors who failed to read the instructions, I have an alternative option.

Opting for a heavy sandbag clean and run as part of the sprint drag carry would get you the explosive power movement you need. You could drop the stupid ball throw, and you also don’t need the drag sleds anymore, nor do you need the turf. Units without specialized kit can knock out the revised sprint drag carry with a just a duffle bag and a couple of ammo or water cans.

When we ran the ACFT Sprint out in Oki, we did it as officer only gains. I told the majors in the battalion it was their job to get all the kit we needed, but in a busy week of much more important tasks, making sure we had the drag sleds in the gym didn’t make the cut. After I insisted they could not ‘phone a friend’ to an NCO for an officer workout, we pivoted. We instead used heavy sand filled duffle bags and, honestly, the whole sprint drag carry was improved. I’ve never had to drag anyone or anything 50 meters in combat — nor have I ever had to do that awkward side shuffle for that matter. But pick up some awkward heavy chunk of shit and run with it over my shoulder? Plenty of times.

Close Combat Jobs Are Different And So Are The Soldiers Who Do Them

This really shouldn’t surprise people, and I don’t think it actually does. Every MOS in the army has its own bell curve, but we should expect to see a right adjusted normal for close combat jobs. And that’s exactly what RAND found:

A 540 ACFT score puts you right about the 50th percentile for ‘close combat’, but close to the top 75th percentile for non-close combat. Both groups have a mean well above the 360 required to pass — 520 versus 488. That’s only a 32-point difference between them though — just 5.3% higher on the overall test.

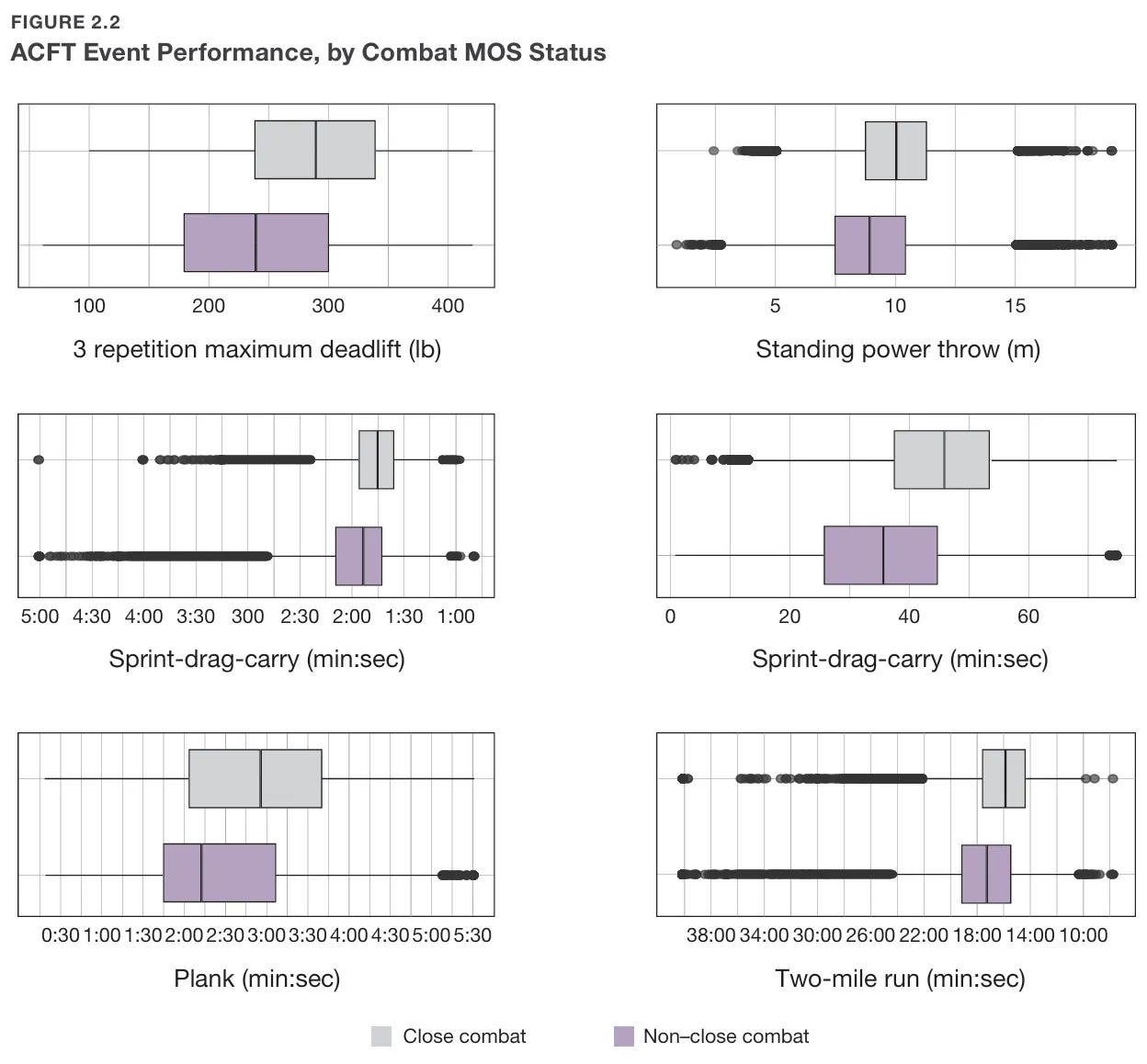

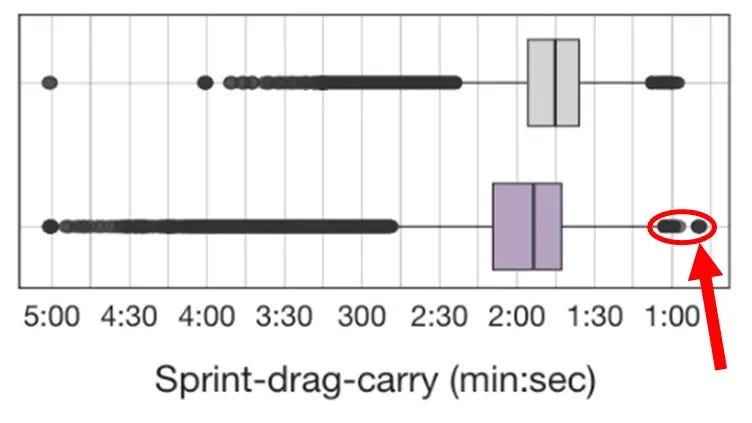

While that left adjustment shows up in individual events, it’s informative to see the error bars.

The bands for close combat are higher, but not overwhelmingly so. In fact, the fastest sprint drag carry scores come from non-close combat MOSs.3 And there are plenty of close combat soldier scores that are at the bottom, far short of a passing a score. So why is the idea of job specific scores so controversial?

As I laid out in the baseline, the ACFT is about assessing your readiness, not your feelings. Different jobs have different minimums for their readiness, with close combat jobs having much more measurable physical requirements. A M1A1 tank’s 120mm round weighs over 18kg (~39.6 pounds), a Javelin Missile ready to fire weighs 22.3 kg (~49.1 pounds), and an M107mm artillery round weighs 43.2kg (~95.2 pounds). The engineer has an H-POMBs, a line charge for clearing mine fields split between two back packs, each of which weighs 23kg (~50.7 pounds).

Every one of those things has to be lifted to be fired. The soldiers picking them up typically have 12.2kg (~27 pounds) of kit on them, plus a rifle — typically 4.5kg (~9.9 pounds) -- and then add on a basic load of ammo (I can’t find an updated basic load table for the XM1186). They also have water, or they really really wish they did. That’s just about 1kg per quart. Adding up all those kilograms is why close combat jobs should have ACFT minimums that are higher than the rest of the army.

But just because a cyber soldier doesn’t need to pick up a javelin missile, doesn’t make him an inferior leader. In fact, subordinating our cyber operators to close combat leaders may be part of why we’re still struggling to operationalize those effects. I don’t know what the minimums should be for the variety of logistics MOSs, but I know I’ve worked for plenty of close combat leaders who clearly didn’t know a damn thing about logistics. If we’re going to accurately assess who’s ready for close combat, we need to separate job specific tasks from presumed leadership potential.

But in our current army culture we’ve decided that because close combat jobs have higher physical demands, those jobs also produce better army leaders.4 This culture is ripe for revision.

Deadlifts Are Good

It probably doesn’t come as much surprise that the deadlift garnered a lot of attention. It’s been the most controversial addition to the test.5 Well based off what RAND found, it’s all about the deadlift.

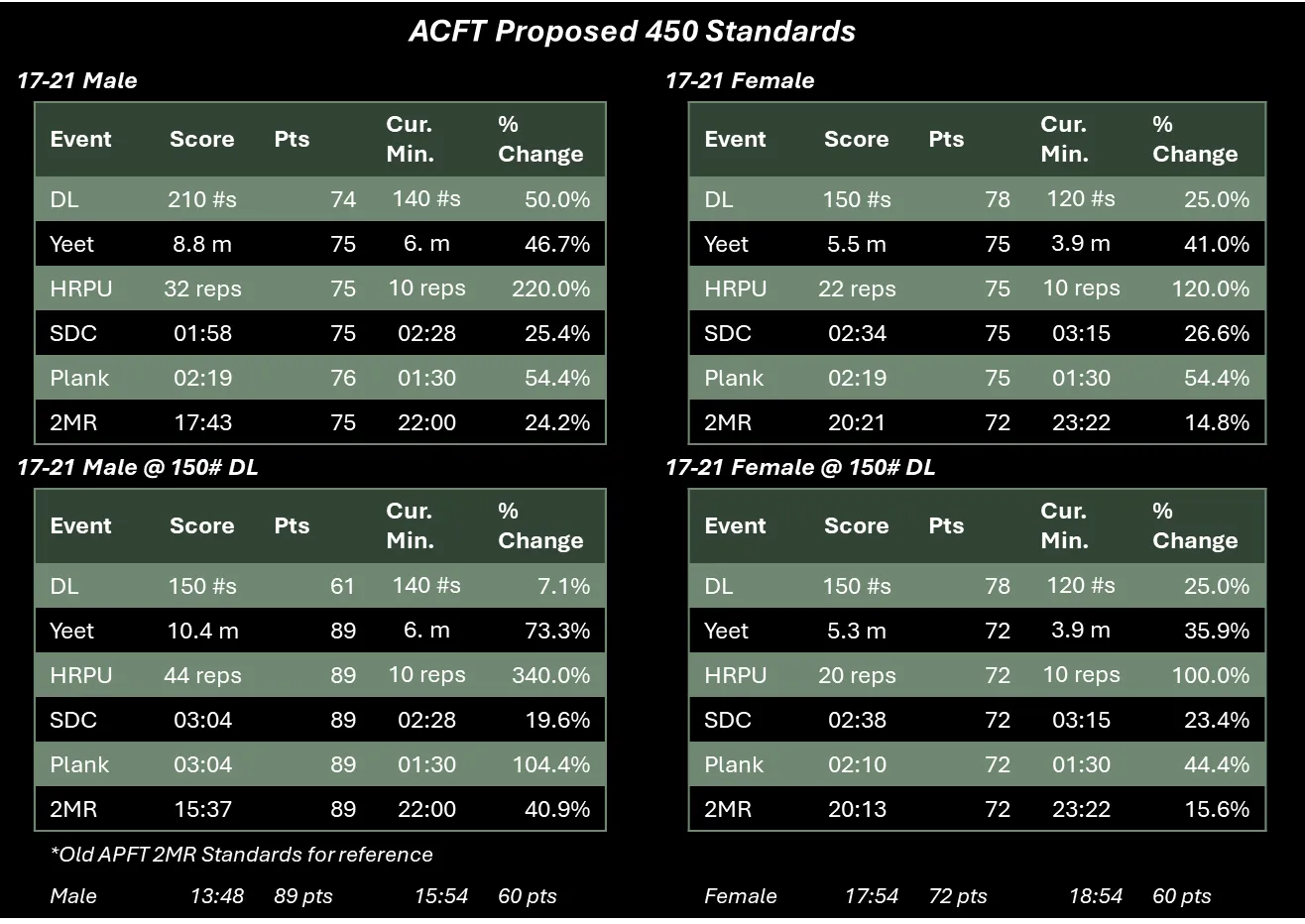

The researchers examined a proposed new minimum for close combat jobs of 450 points overall, with a required 150 pounds minimum deadlift.6 The new minimums can be a bit hard to map, since ACFT 3.0 needs an app and a slide rule to figure out all the permutations. To keep it simple, I’ve pulled the 17–21-year-old proposed mins. These are not actually the hardest standard, but they are the one our newest soldiers will generally have to meet. Check out an app for your own age and gender to see exactly the proposed change would impact you.

The top row of tables is for a minimum of 75 points per-event, while the bottom table examines what changes if you only got the minimum 150-pound deadlift. For males, there is no 75 points in the deadlift, so I opted for the 74-point, 210-pound lift. This means males need to find that extra point somewhere — the easiest place is in the plank. RAND researchers commented on the imbalance between different events:

‘Improving the 2MR from 60 to 61 points requires as much as about 1 minute of improvement, whereas increasing from 60 to 61 on the PLK requires only a 3-second longer hold.’

Changes don’t scale evenly between genders either.

‘For example, to move from 60 to 70 points, a 21-year-old male soldier must increase by 18 repetitions on the HRP, whereas a 27-year-old female soldier only needs 4 additional repetitions.’

But a 150-pound Deadlift is only 61 points for males’ points, which means the soldier must make up the 14 points somewhere. Which is what you see in the lower tables. You can split the 14 points across the other five events, but the easiest way is to just plank for another 45 seconds. I say this based of my experience at CCAP. Despite only a few colonels being able to max the deadlift or the sprint drag carry, just about everyone maxed the plank. A female 150 deadlift is 78 points, which means she can get actually get 3 points less in one of the events and still make the 450 total.

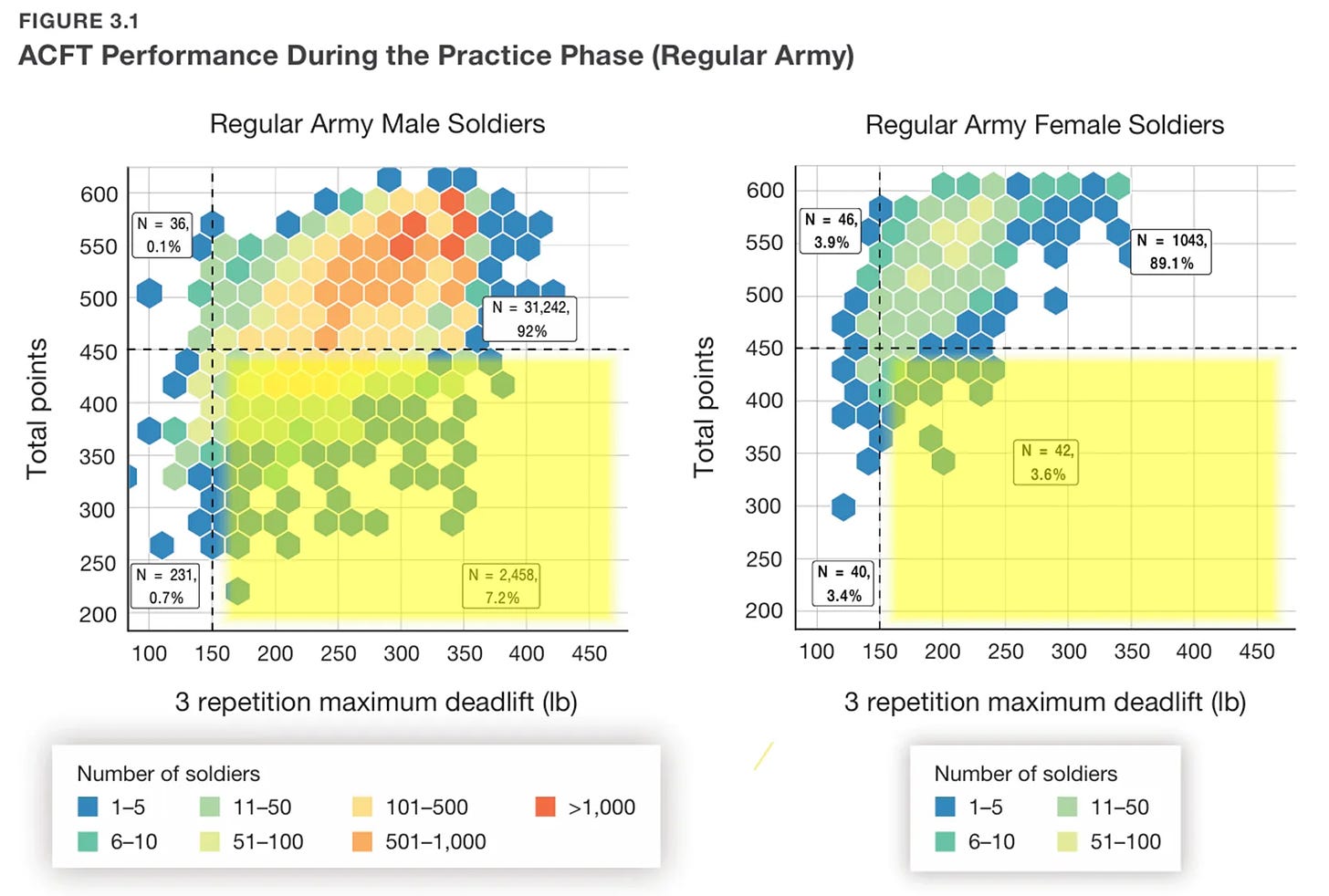

Let’s take a look at what RAND found:

First, females have a markedly smaller dataset, but that’s unlikely to change in the immediate future. They are a minority of the army (just 15.5% of active component), and an even smaller minority of these MOSs, which only opened up to them in the last few years.

And yet look at how messy the males scores are versus the females [yellow highlights added]. If you’re a female who can DL 150 pounds — which on average is a much higher percentage of your overall bodyweight than men — then you are dramatically more likely to be able to crush the other ACFT events. Meanwhile, males have plenty of soldiers who can DL 150 for three reps but then struggle in one or all of the remaining events.

This cleaner female dataset is likely a result of age, but not in the way you’re probably thinking. Deep in the tables at the end of the report you’ll see a slow improvement among females from age 17 to age 36. Then it just crashes. While getting older and getting injured are certainly part of that trend, I think culture has a larger impact. Looking at the data that set the current ACFT standards, soldiers over 36 years old show a marked disinterest in training for the new standards, which is part of why they drop so dramatically.

This is changing though. Fitness norms for females have been changing culturally. Two decades ago, when I was fresh out of high school, women were taking up sports at record levels. However, that trend heavily favored running or cardio sports — track, soccer, tennis, and swimming for example. Women are still increasing their sports patriation, but that cardio culture has been slowly, but consistently, changing. It’s no longer shocking to see a woman with developed lats and shoulders. Functional fitness programs have been seeing increasing growth among female customers. Over the last twelve years, at least half of the people joining me in early morning gym classes have been female.

Millennial and Gen Z women are more likely to lift than Gen X. But that doesn’t mean Gen X women can’t lift. While deployed to Iraq in 2019, we had a female lieutenant colonel who was prepping for CAP.7 This was the first year of CAP and so it wasn’t immediately clear if they’d be doing an APFT or an ACFT. Determined to be ready, she enlisted our support to help make sure she could pass both tests.

She needed help because she was a gazelle. Lean and fast as hell, but not able to do much more than a pair of pull-ups when she started training with us. Over the next six months we met two days a week to go over both the techniques and skills she’d need to develop, with a heavy focus on grip strength and increasing her power. It only took her a single class on the deadlift to pull 140 pounds for the first time. By the time she left she was able to deadlift 210-pound (95.3kg) three times — the old ‘black’ standard.

So, when the RAND researchers found the deadlift one rep standard could likely be closer to 200 pounds, I wasn’t surprised. As Henry Rollins quipped, ‘The iron never lies to you… Friends may come and go. But two hundred pounds is always two hundred pounds.’ The RAND study found the same, with the highest concentration of female scores right there over 200 pounds. For what it’s worth, the vast majority of female soldiers I have served with can achieve both the 450 and a 150-pound deadlift. But more specifically, every single one of the females in close combat MOSs I know can achieve them without excessive effort. That’s anecdote, not data though.

The predictive power of the deadlift wasn’t just in the ACFT. In examining the close combat OPATs (Occupational Physical Assessment Test), tests given to new recruits at their initial MOS training, RAND found strong correlational prediction. The OPAT uses a single rep deadlift and found a 140-pound (63.5kg) deadlift could predict with 76% accuracy who would and would not complete the combat-related tasks at the end of their initial training. That’s one hell of an indicator. Indeed, RAND researchers proposed that, as the ACFT is a three-rep test, the OPAT could likely increase their standard to 200 pounds and see an increase in its predictive accuracy.

The deadlift is a good indicator of readiness overall. With females it appears to be heavily correlational. And females likely have more room to improve their scores than males as the culture of lifting continues to expand and new soldiers learn to be ready.

We Need To Talk About The National Guard

I’m not nearly as confident about the National Guard. RAND, trying to put it delicately, said:

‘These findings suggest that ARNG and USAR may have pass rates that are considerably lower than the Regular Army.’

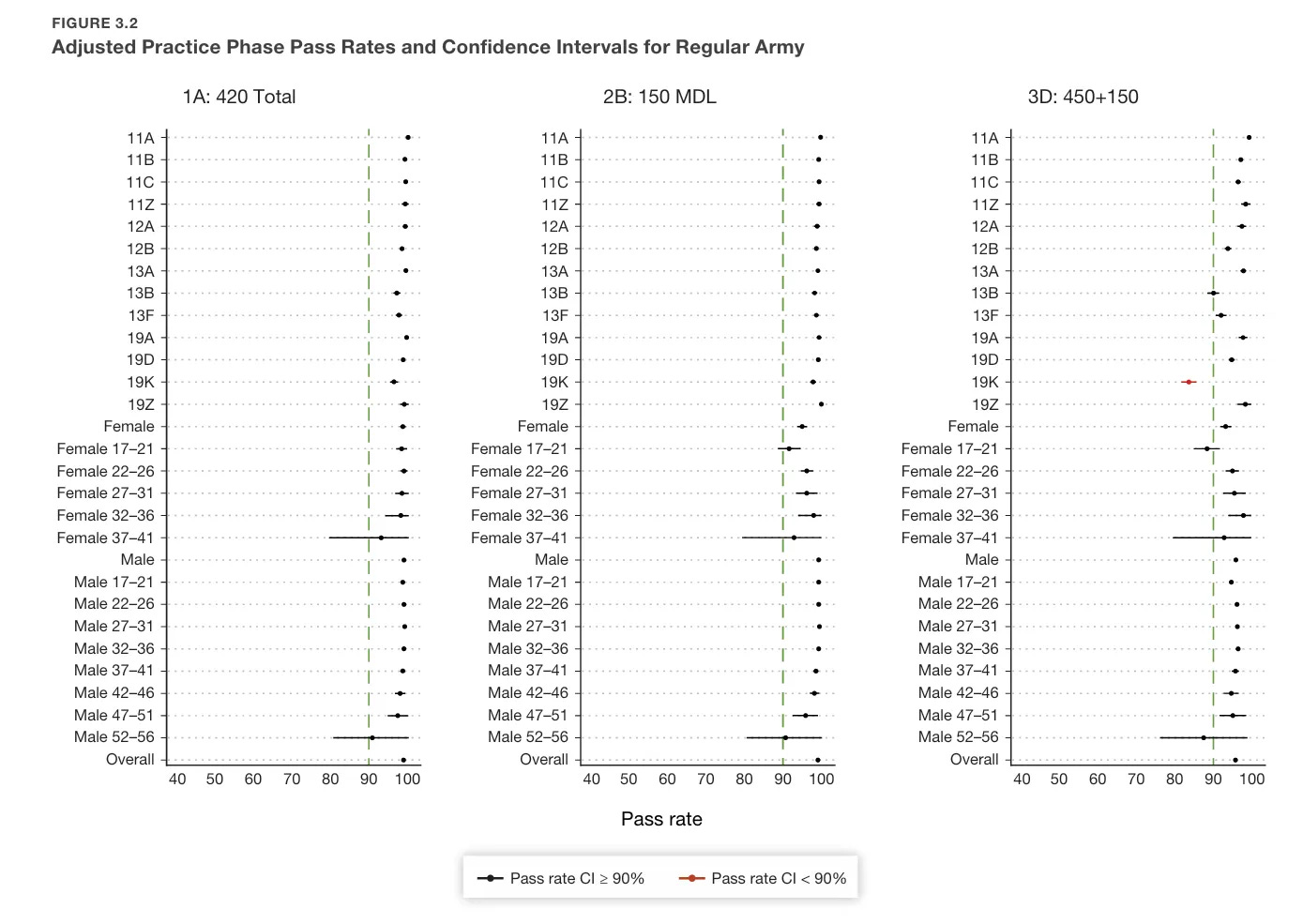

Here’s the Regular Army:

Aside from the already addressed females over 36, the only real problem children are our 19Ks — tankers. Based of my limited experience back when I was mech, this checks out.

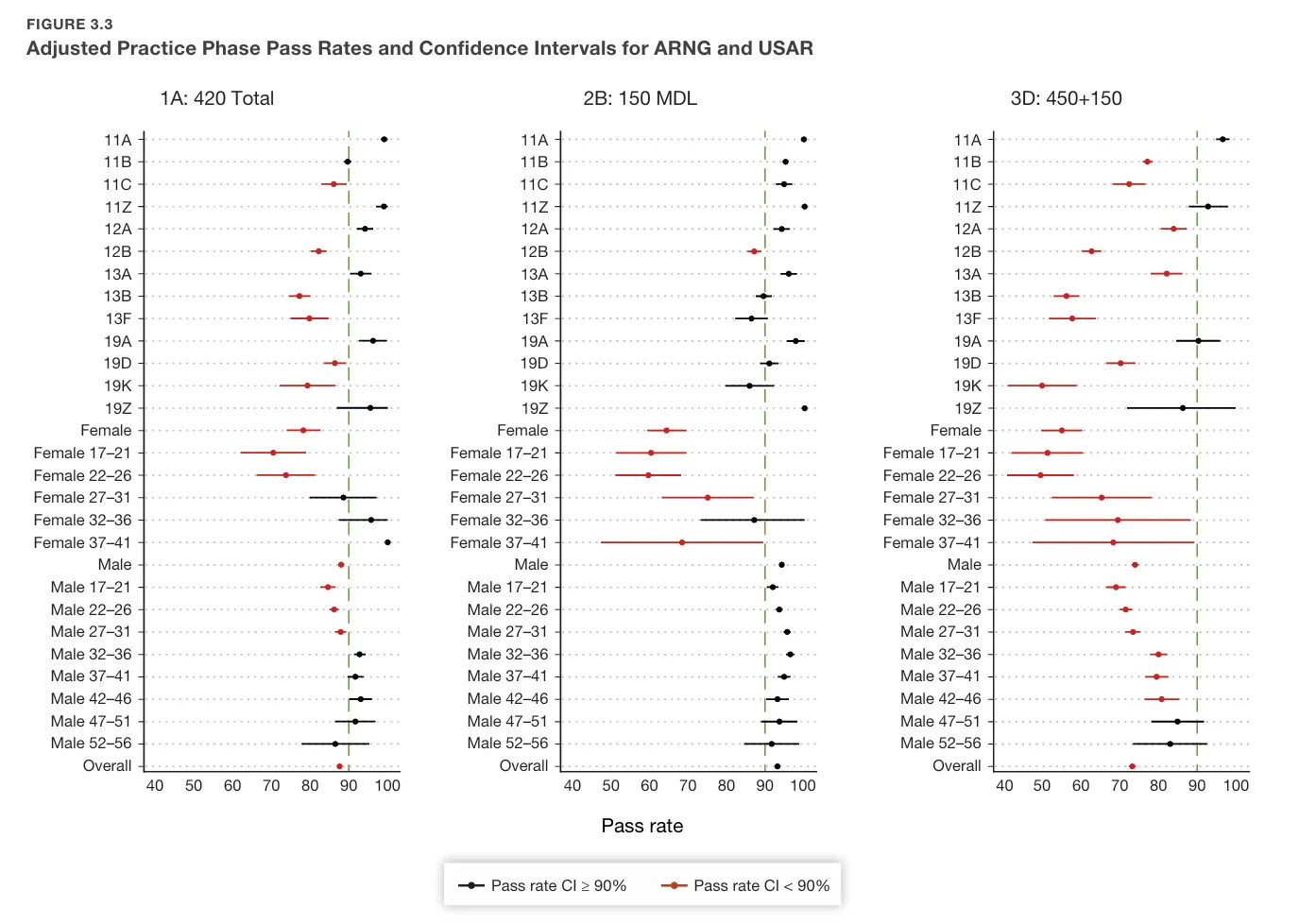

Now here’s the National Guard.

What the hell is happening? Clearly our National Guard is hurting. But why? I don’t know and the RAND researchers didn’t provide a reason either. We’ve relied on the National Guard to fill the force throughout twenty years of ‘small wars.’ But our plans for big wars with peer threats like China and Russia depend even more on both the National Guard and the reserves. These scores imply we’ve got a huge hole in our swing. I don’t have the answer to why. I do have a suggestion for one way to fix it, but most people aren’t going to like it.

Back at the beginning of their report, RAND disclosed they had pulled Special Forces data out of the set.

‘Although Special Forces MOSs (18 series) were included in the mandate, we excluded these MOSs in the evaluation of pass rates because our analysis showed that soldiers within the Special Forces community have uniformly high ACFT scores.’

While I’d love to bathe in that sentence for a while, there’s nothing inherently fitter about Special Forces soldiers.8 SFAS doesn’t find the fastest or the strongest, but it does screen for the self-motivated.9 You don’t pass the Star Course on land navigation ability alone. In addition to not getting lost in the dark, the swamps, and the dark swamps of Camp Mackall, you also need to get up and move with a heavy pack for ten hours without anyone else keeping an eye on you or telling you to get off your ass.

I’d be interested to see how Special Forces and Regular Army ACFT scores differ from our previous scores in the APFT. The new test is a better assessment of readiness, but it also measures who got ready (more on that in a bit). National guard units aren’t going to get a soldier ready for combat one weekend a month. Those national guard soldiers need to be doing a lot of self-motivated fitness if they want to be ready.

And that delta between SF and the regular army is also worth calling out. RAND researchers made an unfounded claim when they argued:

… absent any performance evaluation data that indicate performance deficiencies, it is assumed that soldiers currently serving in close combat MOSs are performing to a minimally acceptable standard. Therefore, any differences in subgroup pass rates on new standards would need to be justified by rigorous evidence collected from validation studies.

This is not a safe assumption. SFAS results have been hugely indicative of a negative fitness trend in the regular army close combat units. Our in-service recruiting has been dwarfed by our 18X — direct recruits — production for years. This is because a significant percentage of active army soldiers can’t meet the minimum fitness standards to start SFAS, never mind complete it. The results have been so poor that the SORB (Special Operations Recruiting Battalion) have found whole bases to be not worth the travel cost of a recruiting visit.

Regardless, those National Guard results are stark, and probably won’t get as much press attention as the deadlift.

But I need time to get ready…

The RAND study opens with:

The Army Combat Fitness Test (ACFT), consisting of six events (Table 1.1), was implemented as the official fitness test in the Regular Army on October 1, 2022, and for the reserve components in April 2023.

Except that’s not really true. Later on they track the process of both the roll out and the assessments done on the ACFT. ACFT 1.0 — the one with the leg tucks —came out back in fiscal year 2018. We’re now in 2025 and yet we continue to see the excuses that the ACFT is ‘new’ and needs a glidepath to onboard soldiers.

In perhaps the most obvious thing anyone wrote ever, the RAND study found:

Soldiers have been shown to improve with experience.

But more specifically:

These soldiers who previously did not meet the higher standard improved, on average, by 15.8 points relative to their most recent test 10–14 months pre-Practice Phase, with a 51.8-point increase for female soldiers ages 17–21 in the Regular Army.

I have taken an 'above average' number of ACFTs, despite it being on the glide path. The test was formally rolled out with the start of calendar year 2021 and I have nine ACFTs under my belt, just one more than I should have if I was taking two ACFTs a year. And yet I am probably in the top 25% of total ACFTs in the army, surpassed by those who have to regularly administer them.10

We fought all of World War 2 in less time than the ACFT has been around. Too many leaders didn’t get ready. Too many leaders still aren’t.

In a discussion among a random sample of soldiers, RAND posited how changes could and should be implemented. One thing they reported was ‘…company commanders and other leaders need to be aware of resources and request them for their units, and that H2F resources are under utilized in some units’. This is surely true, but also a symptom. Because just like the data-illiterate, leaders who cling to gazelle definitions of fitness still dominate our commands.

The RAND Study concludes it is key we address a perceived ‘…lack of transparency in test-related communication’ and ‘Leadership challenges for implementing new standards’. Given my limited success in moving the needle on data-literacy, I’m not certain how successful we’ll be on fitness. Regardless, Downrange Data is my attempt to reach as wide an audience as I can on both of these issues.

Closing Thoughts

RAND’s study was a good one, with several key findings army leaders should be reading:

‘…higher standards may support objectives to reinforce a fitness culture but may require more resources for training to achieve those standards.’

and:

‘Changing the standard could result in soldiers changing how they train and developing additional test-taking strategies, which can have both positive and negative impacts that are not foreseeable until full implementation of the new standards.’

Training for the test isn’t a bad thing if its a good test. The ACFT isn’t perfect, but it is better. Team ‘Sprint Clean Carry’! Who’s coming with me?!

We still haven’t figured out what we want to do about how age impacts MOSs (more on this in G.9). But the ACFT is a better test than the APFT and it does more to drive real, measurable readiness. But this change also requires leaders to learn knew things, to be humble and fail, but fail forward, improving both ourselves and the soldiers we command.

RAND provides several suggestions on how to facilitate higher standards. Two in particular caught my eye:

Clarify ACFT goals. Promote acceptance of higher ACFT standards by establishing a clear and consistent message across all organizational levels, which includes transparent policies for failure to meet close combat ACFT standards.

Tell soldiers why we’re changing. The army could also benefit from taking a look at the experiences of the Ukrainian army and the Israelis, both fresh off high intensity and ongoing combat operations. This may provide anecdotes that help illustrate the need for change, and possibly propose updates to the operational demands we use to set our standards.

Remedial assessments: Use MOS-specific physically demanding tasks as a test for soldiers who do not meet the higher ACFT standard (these task-based tests should be standardized for each MOS).

I think this one is particularly interesting. You could have a pool of say, six MOS specific skills a soldier needs to be able to do. If a soldier fails to meet an ACFT minimum at the 450, let them demand ‘trial by combat’, where they are required to demonstrate a combat task without advance knowledge of which one it will be. This reinforces that the ACFT, and our fitness, is ultimately about being ready.

In the end RAND has given us a lot of data to work with. But it’s up to us to take advantage of it. We kept horse cavalry until 1942 because leaders didn’t like or want change. Over the last year I heard multiple US Army four-star general officers dismiss the impact that drones are having on today’s battlefield. Apparently, our army doesn’t need to change because ‘that war is just two bad armies fighting’ and ‘our tanks drive fast’.

Leaders need to lead change. But first, they have to want to.

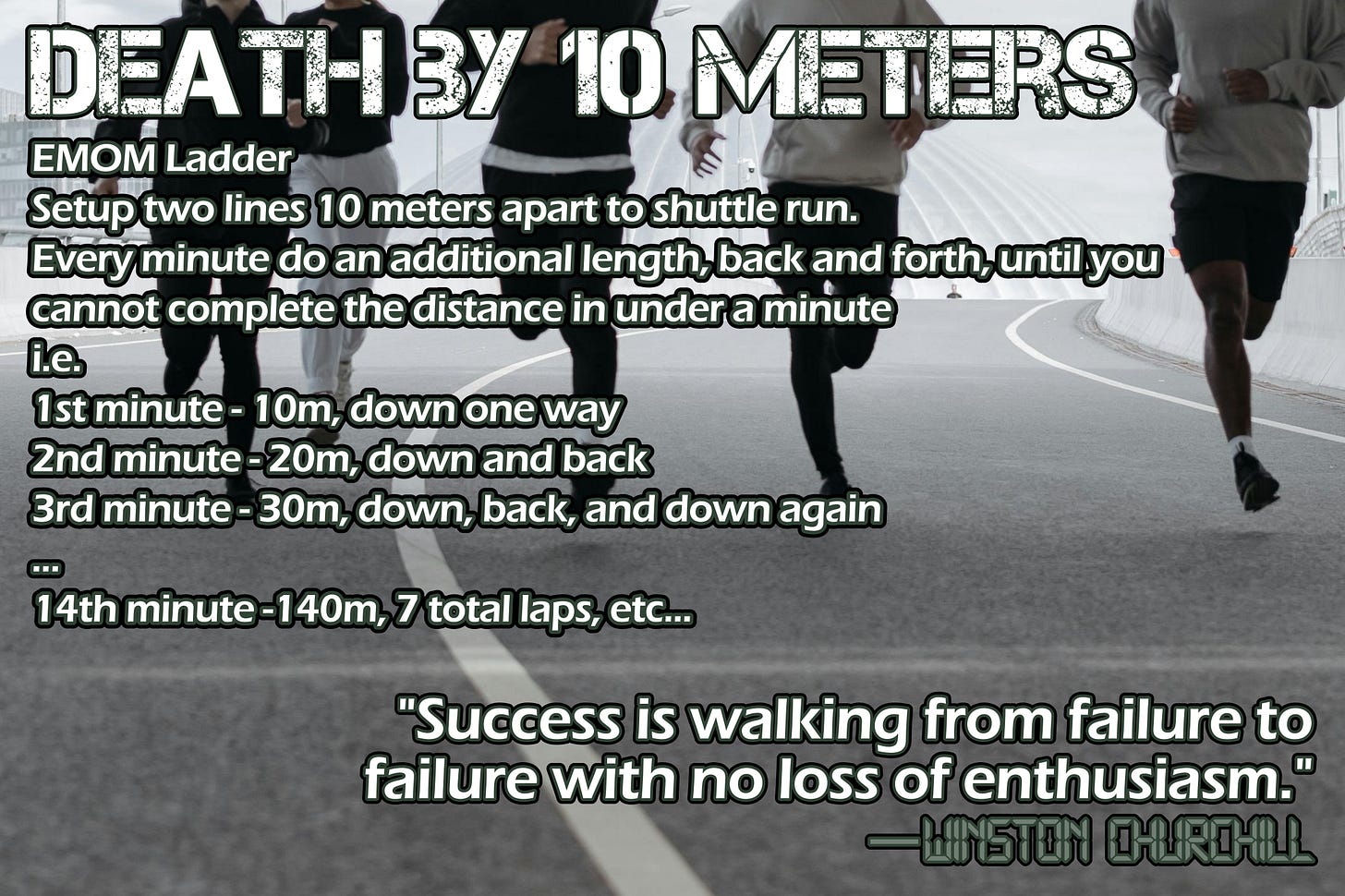

Death by 10m

RAND’s Study found the OPAT ‘Beep Test’ demonstrated good correlation with fitness and readiness for combat tasks. They even proposed finding an elaborate formula to translate the ‘beep test’ into new two-mile run standards. I have no idea why we don’t just do the beep test instead, but I actually prefer “Death By 10 Meters” over the beep test. This is because it scales faster, so I run less.

Do not ever let anyone in the army get away with decrying ‘everyone gets a trophy’ culture. We are the worst.

While I am — and was — in favor of the job-based standards, I can concede the roll-out was rocky. Was a non-close combat MOS soldier in a close combat unit held to that standard, or to their MOS? Why were SF chiefs (180A) held to a lower standard than senior SF NCOs (18Zs)? The rollout also wasn’t helped by a significant proportion of senior officers and NCOs who sought to sabotage the changes. That’s not just my opinion but is visible in a clear drop off in the standards — which were built off those diagnostic scores — for those soldiers with over fifteen years of service.

Some people might argue the Leg Tuck was more controversial, but since we just summarily swapped that out for the unvalidated plank, I’d argue the deadlift invites more of a fight.

RAND examined eight different potential changes, and the army selected this one for the practice standard.

Command Assessment Program. An assessment run in the fall where the Army evaluates the next generation of the Command Select List (CSL) leaders among its Lieutenant Colonels, Colonels, and Sergeants Major.

Every GB I know can name at least one other GB who really let themselves go.

Special Forces Assessment and Selection. The 24-day course candidates attend that tests their ability to train to become a Special Forces soldier - a Green Beret.

Our First Sergeant at my last headquarters took an ACFT every other week when the headquarters company ran one. Guy was a beast.

As you've discussed previously I believe, part of the issue is that the roll-out happened during COVID. But I think another issue was the inability to hold people accountable for either good or bad scores. While I understand that you can't kick people out for an untested test, the number of individuals who just phoned in the test during the trial window (pre-2022ish) was high in my experience. So I'd argue that the data prior to the test being a test of record is bad data.